In this article, I look inside a chip in the IBM 3274 Control Unit.1 But before I discuss the chip, I need to give some background on mainframes. (I didn't completely analyze the chip, so don't expect a nice narrative or solid conclusions.)

IBM's vintage mainframes were extremely underpowered compared to modern computers; a System/370 mainframe ran well under 1 million instructions per second, while a modern laptop executes billions of instructions per second. But these mainframes could support rooms full of users, while my 2017 laptop can barely handle one person.2 Mainframes achieved their high capacity by offloading much of the data entry overhead so the mainframe could focus on the "important" work. The mainframe received data directly into memory in bulk over high-speed I/O channels, without needing to handle character-by-character editing. For instance, a typical data entry terminal (a "3270") let the user update fields on the screen without involving the computer. When the user had filled out the screen, pressing the "Enter" key sent the entire data record to the mainframe at once. Thus, the mainframe didn't need to process every keystroke; it only dealt with complete records. (This is also why many modern keyboards have an "Enter" key.)

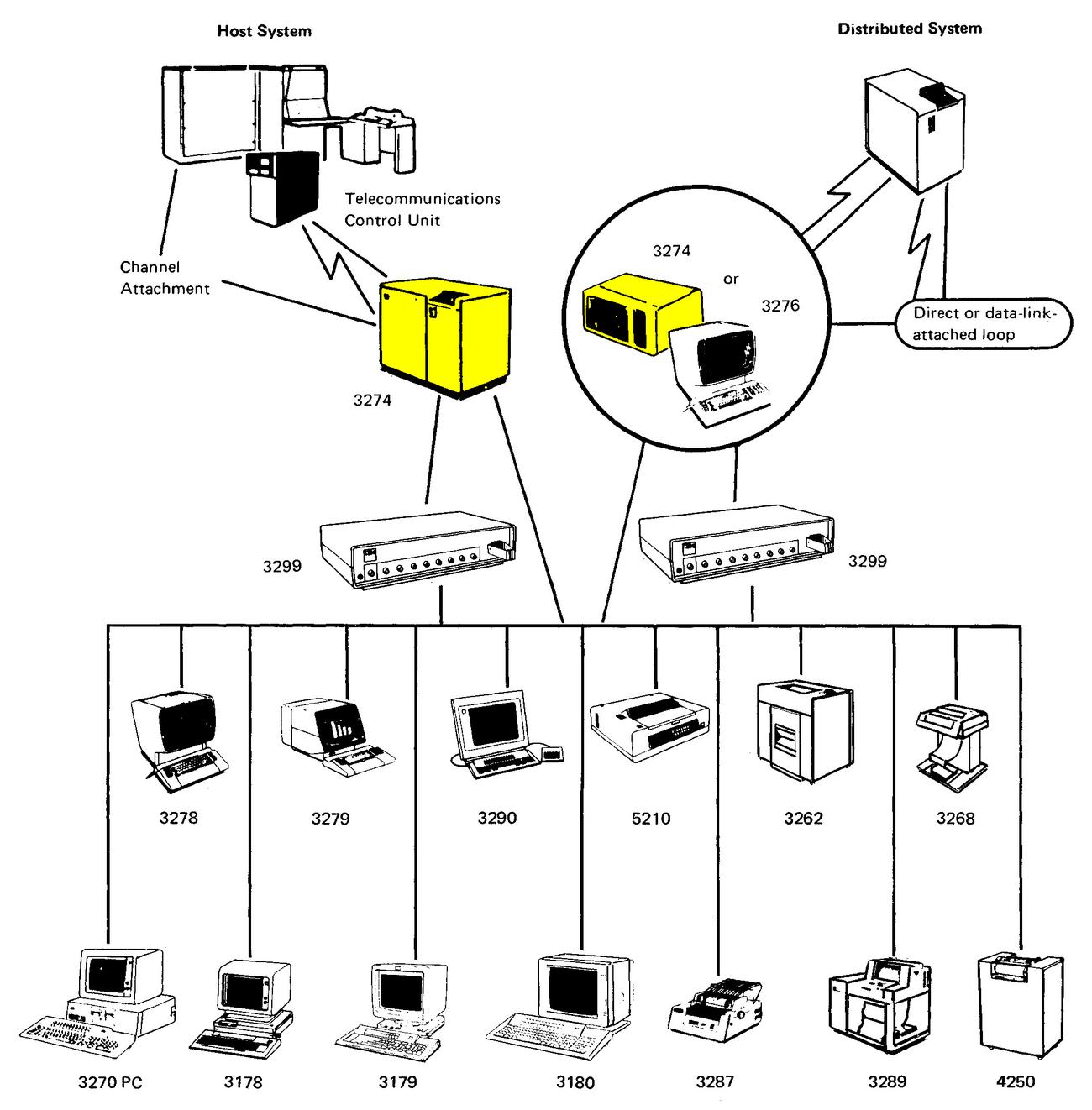

But that was just the beginning of the hierarchy of offloaded processing in a mainframe system. Terminals weren't attached directly to the mainframe. You could wire 16 terminals to a terminal multiplexer (such as the 3299). This would in turn be connected to a 3274 Control Unit that merged the terminal data and handled the network protocols. The Control Unit was connected to the mainframe's channel processor which handled I/O by moving data between memory and peripherals without slowing down the CPU. All these layers allowed the mainframe to focus on the important data processing while the layers underneath dealt with the details.3

The 3274 Control Unit (highlighted above) is the source of the chip I examined. The purpose of the Control Unit "is to take care of all communication between the host system and your organization's display stations and printers". The diagram above shows how terminals were connected to a mainframe, with the 3274 Control Unit (indicated by arrows) in the middle. The 3274 was an all-purpose box, handling terminals, printers, modems, and encryption (if needed). It could communicate with the mainframe at up to 650,000 characters per second. The control unit below (above) is a boring beige box. The control panel is minimal since people normally didn't interact with the unit. On the back are coaxial connectors for the lines to the terminals, as well as connectors to interface with the computer and other peripherals.

The Keystone II board

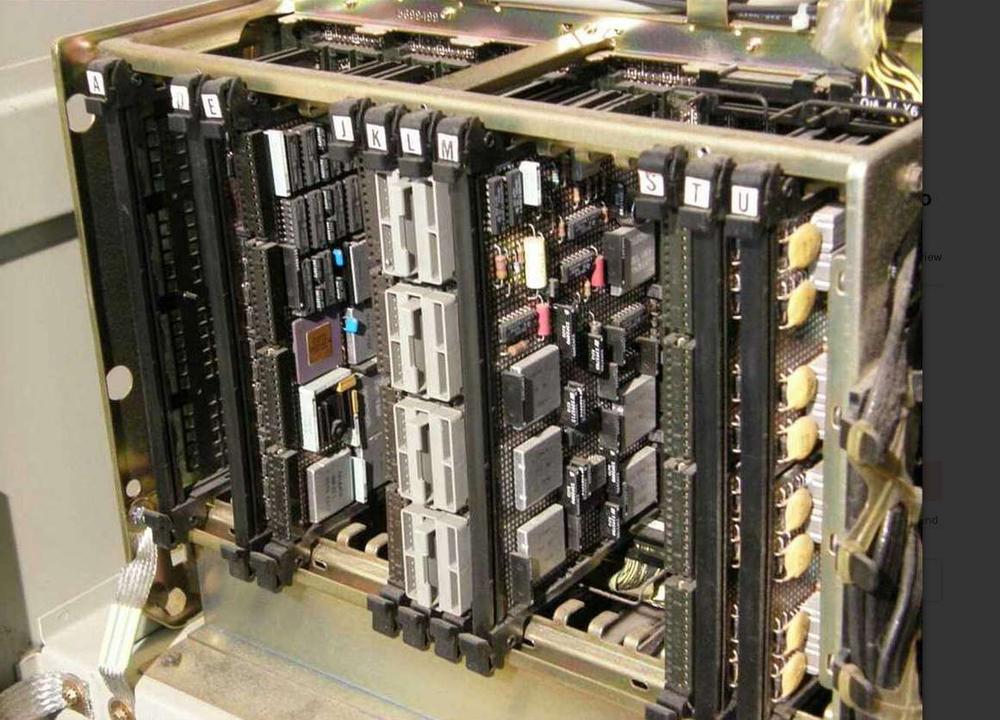

In 1983, IBM announced new Control Unit models with twice the speed: these were the Model 41 and Model 61. These units were built around a board called Keystone II, shown below. The board is constructed with IBM's peculiar PCB style. The board is arranged as a grid of squares with the PCB traces too small to see unless you zoom in. Most of the decoupling capacitors are in IBM's thin, rectangular packages, although I see a few capacitors in more standard blue packages. IBM is almost a parallel universe with its unusual packaging for ICs and capacitors as well as the strange circuit board appearance.

Most of the chips on the board are IBM chips packaged in square aluminum cans, known as MST (Monolithic System Technology). The first line on each package is the IBM part number, which is usually undocumented. The empty socket can hold a ROS chip; ROS is Read-Only Store, known as ROM to people outside IBM. The Texas Instruments ICs in the upper right are easier to identify; the 74LS641 chips are octal bus transceivers, presumably connecting this board to the rest of the system. Similarly, the 561 5843 is a 74S240 octal bus driver while the 561 6647 chips are 74LS245 octal bus transceivers.

The memory chips on the left side of this board are interesting: each one consists of two "piggybacked" 16-kilobit DRAM chips. IBM's part number 8279251 corresponds to the Intel 4116 chip, originally made by Mostek. With 18 piggybacked chips, the board holds 64 kilobytes of parity-protected memory.

The photo below shows the Keystone II board mounted in the 3274 Control Unit. The board is in slot E towards the left and the purple Motorola IC is visible.

The Motorola/IBM chip

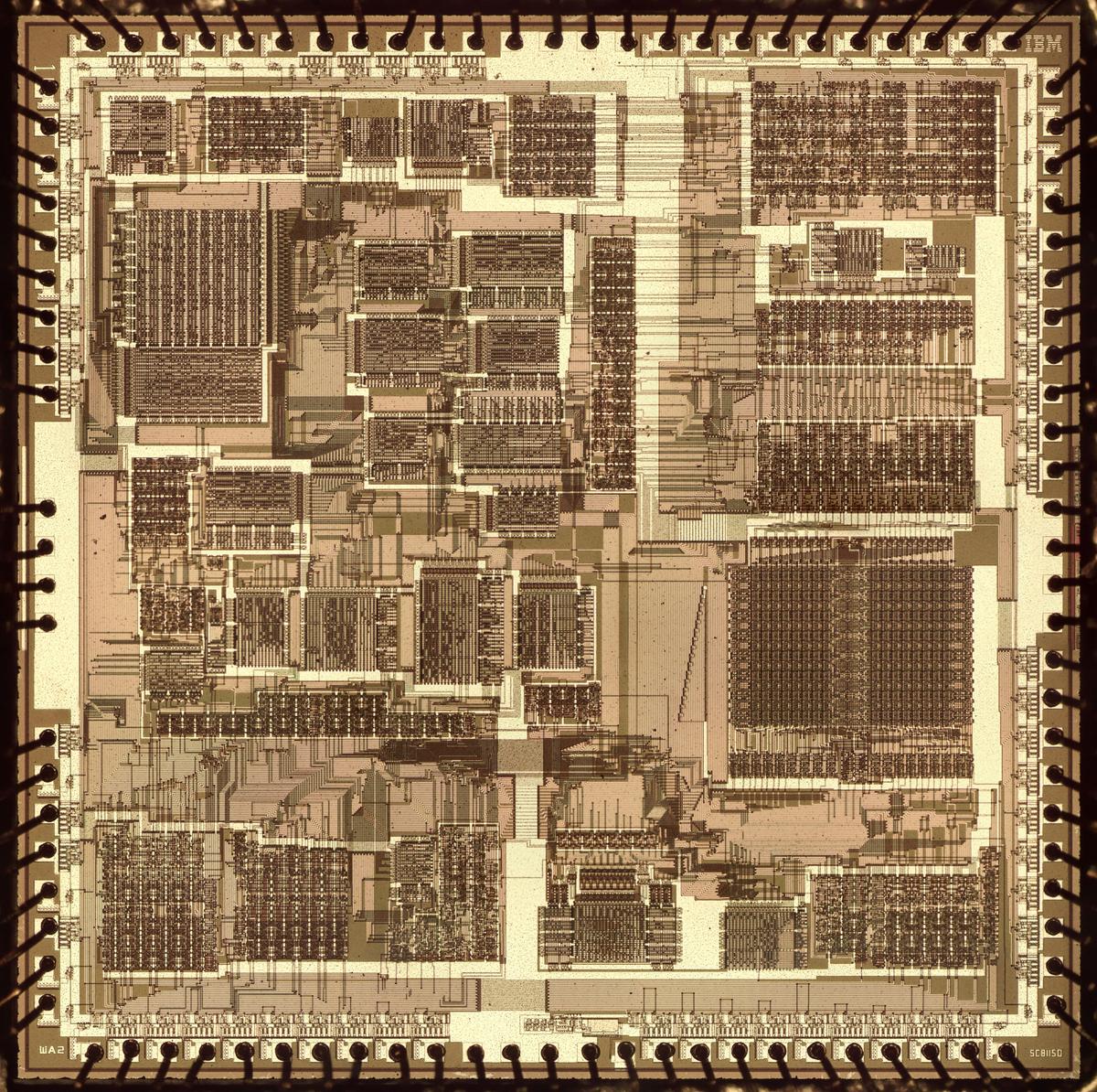

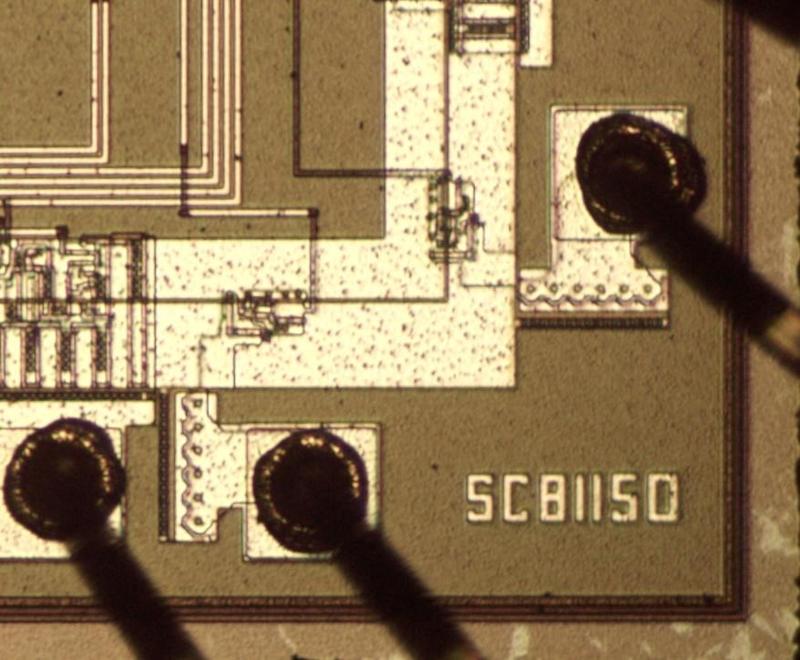

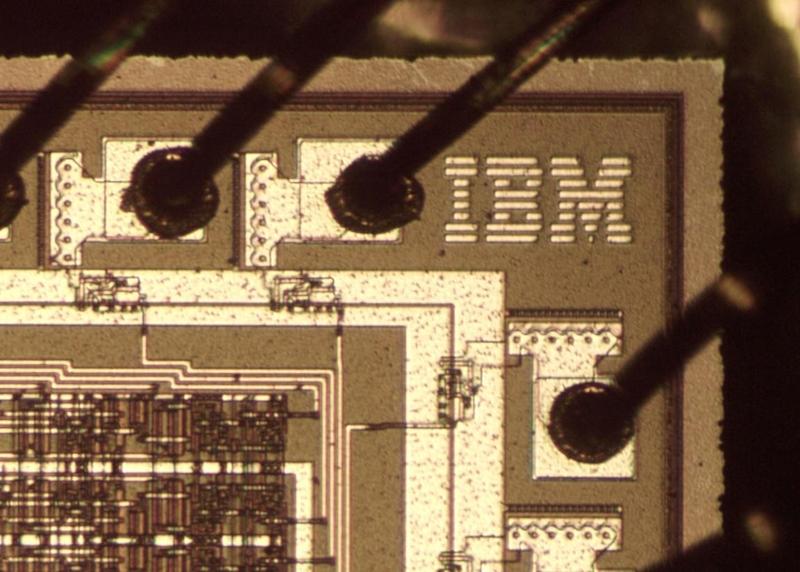

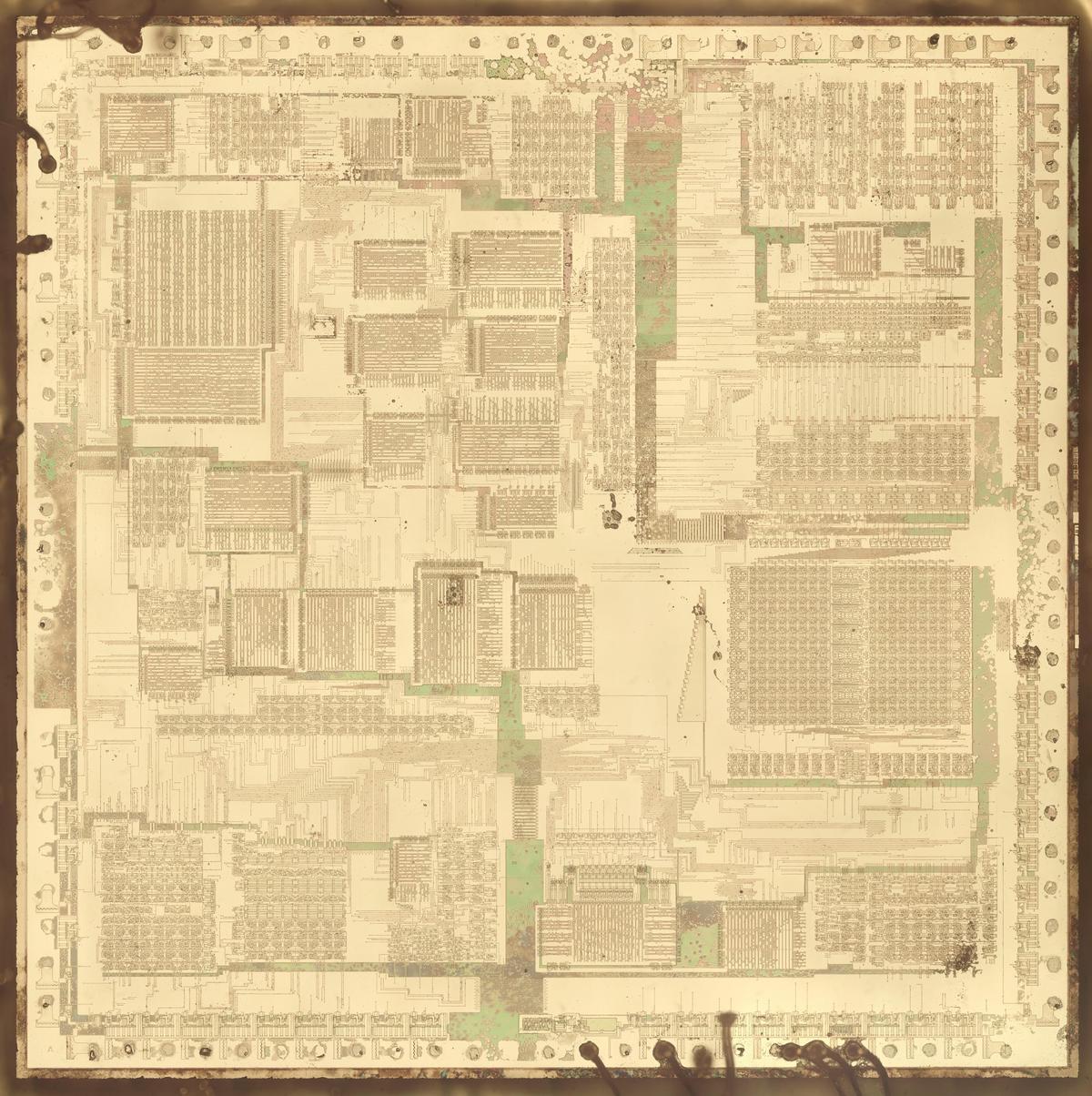

The board has a Motorola chip in a purple ceramic package; this is the chip that I examined. Popping off the golden lid reveals the silicon die underneath. The package has the part number "SC81150R", indicating a Motorola Special/Custom chip. This part number is also visible on the die, as shown below.

While the outside of the IC is labeled "Motorola", there are no signs of Motorola internally. Instead, the die is marked "IBM" with the eight-striped logo. My guess is that IBM designed the chip and Motorola manufactured it.

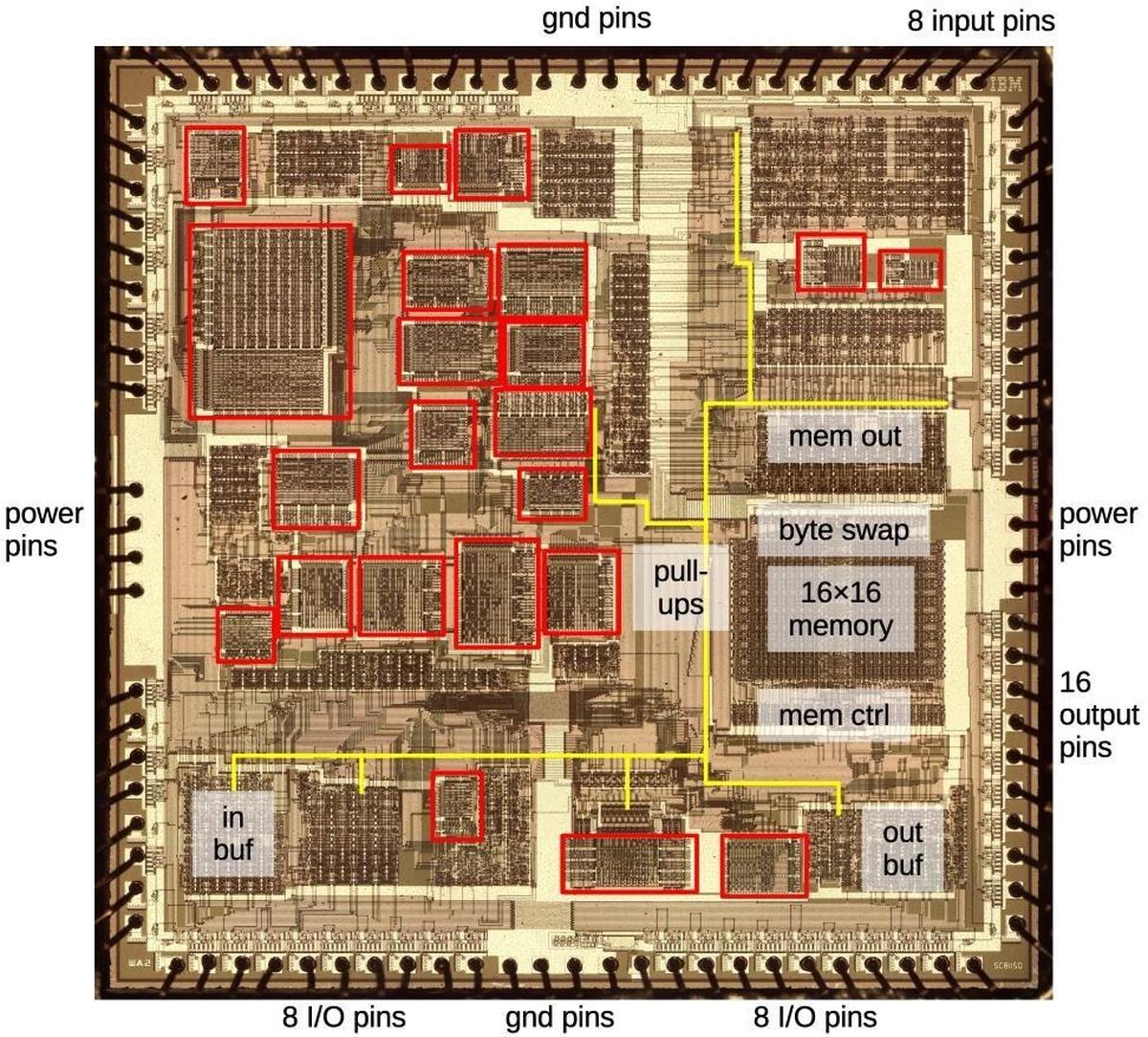

The diagram below shows the chip with some of the functional blocks identified. Around the outside are the bond pads and the bond wires that are connected to the chip's grid of pins. At the right is the 16×16 block of memory, along with its associated control, byte swap, and output circuitry. The yellowish-white lines are the metal layer on top of the chip that provides the chip's wiring. The thick metal lines distribute power and ground throughout the chip. Unlike modern chips, this chip only has a single metal layer, so power and ground distribution tends to get in the way of useful circuitry.

The chip is centered around a 16-bit bus (yellow line) that connects many part of the chip. To write to the bus, a circuit pulls bus lines low. The bus lines are kept high by default by 16 pull-up transistors. This approach was fairly common in the NMOS era. However, performance is limited by the relatively weak pull-up current, making bus lines slow to go high due to R-C delays. For higher performance, some chips would precharge the bus high during one clock cycle and then pull lines low during the next cycle.

The two groups of I/O pins at the bottom are connected to the input buffer on the left and the output buffer on the right. The input buffer includes XOR circuits to compute the parity of each byte. Curiously, only 6 bits of the inputs are connected to the main bus, although other circuits use all 8 bits. The buffer also has a circuit to test for a zero value, but only using 5 of the bits.

I've put red boxes around the numerous PLAs, which can be identified by their grids of transistors. This chip has an unusually large number of PLAs. Eric Schlaepfer hypothesizes that the chip was designed on a prototype circuit board using commercial PAL chips for flexibility, and then they transferred the prototype to silicon, preserving the PLA structure. I didn't see any obvious structure to the PLAs; they all seemed to have wires going all over.

The miscellaneous logic scattered around the chip includes many latches and bus drivers; the latch circuit is similar to the memory cells. I didn't fully reverse-engineer this circuitry but I didn't see anything that looked particularly interesting, such as an ALU or counter. The circuitry near the PLAs could be latches as part of state machines, but I didn't investigate further.

I was hoping to find a recognizable processor inside the package, maybe a Motorola 6809 or 68000 processor. Instead, I found a complicated chip that doesn't appear to be a processor. It has a 16×16 memory block along with about 20 PLAs (Programmable Logic Arrays), a curiously large number. PLAs are commonly used in processors for decoding instructions, since they can match bit patterns. I couldn't find a datapatch in the chip; I expected to see the ALU and registers organized in a large but regular 8-bit or 16-bit block of circuitry. The chip doesn't have any ROM4 so there's no microcode on the chip. For these reasons, I think the chip is not a processor or microcontroller, but a specialized data-handling chip, maybe using the PLAs to interpret bits of a protocol.

The chip is built with NMOS technology, the same as the 6502 and 8086 for instance, rather than CMOS technology that is used in modern chips. I measured the transistor features and the chip appears to be built with a 3.5 µm process (not nm!), which Motorola also used for the 68000 processor (1979).

The memory buffer

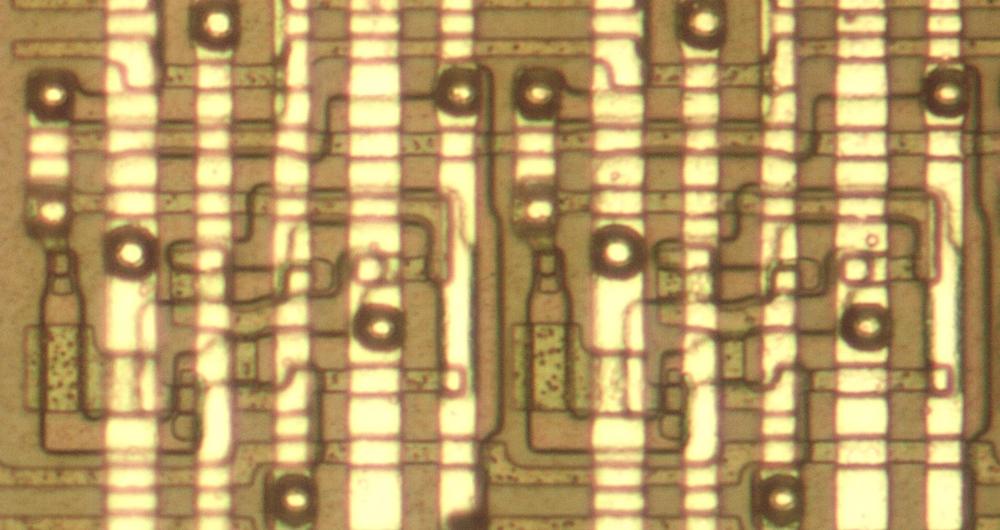

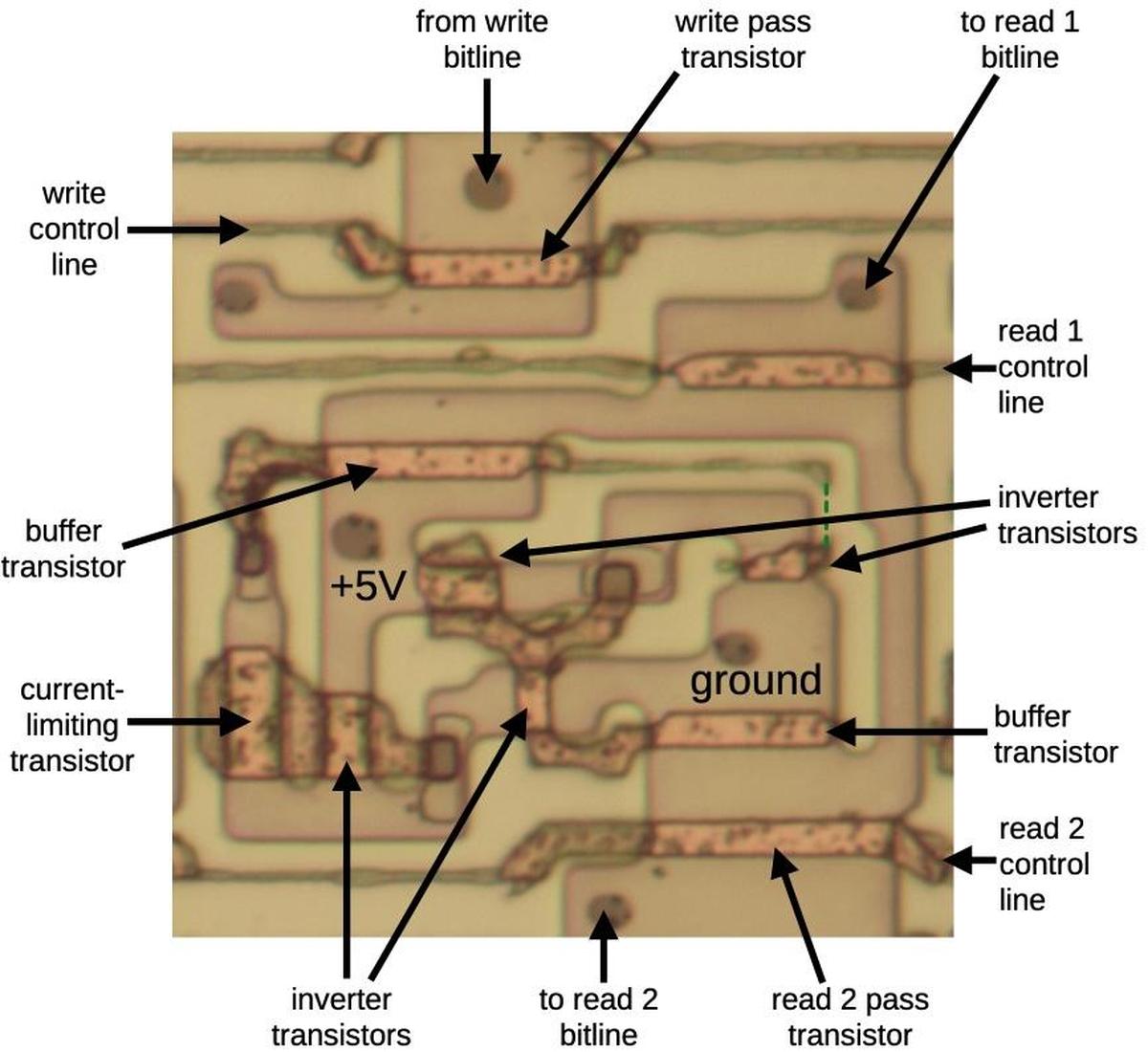

The chip has a 16×16 memory buffer, which could be a register file or a FIFO buffer. One interesting feature is that the buffer is triple-ported, so it can handle two reads and one write at the same time. The buffer is implemented as a grid of cells, each storing one bit. Each row corresponds to a 16-bit word, while each column corresponds to one bit in a word. Horizontal control lines (made of polysilicon) select which word gets written or read, while vertical bit lines of metal transmit each bit of the word as it is written or read.

The microscope photo below shows two memory cells. These cells are repeated to create the entire memory buffer. The white vertical lines are metal wiring. The short segments are connections within a cell. The thicker vertical lines are power and ground. The thinner lines are the read and write bit lines. The silicon die itself is underneath the metal. The pinkish regions are active silicon, doped to make it conductive. The speckled golden lines are regions are polysilicon wires between the silicon and the metal. It has two roles: most importantly, when polysilicon crosses active silicon, it forms the gate of a transistor. But polysilicon is also used as wiring, important since this chip only has one layer of metal. The large, dark circles are contacts, connections between the metal layer and the silicon. Smaller square regions are contacts between silicon and polysilicon.

It was too difficult to interpret the circuits when they were obscured by the metal layer so I dissolved the metal layer and oxide with hydrochloric acid and Armour Etch respectively. The photo below shows the die with the metal removed; the greenish areas are remnants in areas where the metal was thick, mostly power and ground supplies. The dark regions in this image are regions of doped silicon. These are the active areas of the chip, showing the blocks of circuitry. There are also some thin lines of polysilicon wiring. The memory buffer is the large block on the right, just below the center.

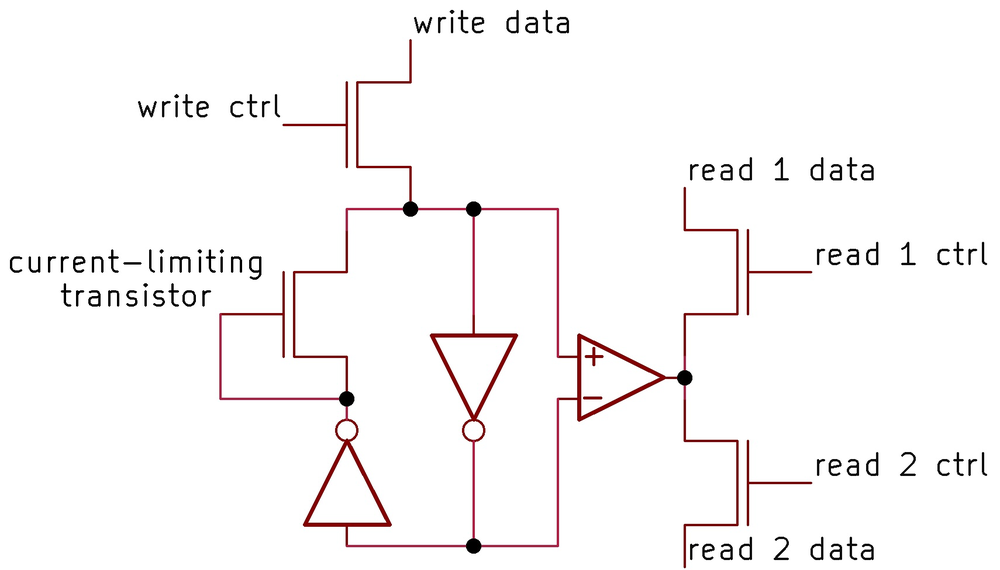

Like most implementations of static RAM, each storage cell of the buffer is implemented with cross-coupled inverters, with the output of one inverter feeding into the input of the other. To write a new value to the cell, the new value simply overpowers the inverter output, forcing the cell to the new state. To support this, one of the inverters is designed to be weak, generating a smaller signal than a regular inverter. Most circuits that I've examined create the inverter by using a weak transistor, one with a longer gate. This chip, however, uses a circuit that I haven't seen before: an additional transistor, configured to limit the current from the inverter.

The schematic below shows one cell. Each cell uses ten transistors, so it is a "10T" cell. To support multiple reads and writes, each row of cells has three horizontal control signals: one to write to the word, and two to read. Each bit position has one vertical bit line to provide the write data and two vertical bit lines for the data that is read. Pass transistors connect the bit lines to the selected cells to perform a read or a write, allowing the data to flow in or out of the cell. The symbol that looks like an op-amp is a two-transistor NMOS buffer to amplify the signal when reading the cell.

With the metal layer removed, it is easier to see the underlying silicon circuitry and reverse-engineer it. The diagram below shows the silicon and polysilicon for one storage cell, corresponding to the schematic above. (Imagine vertical metal lines for power, ground, and the three bitlines.)

The output from the memory unit contains a byte swapper. A 16-bit word is generated with the left half from the read 1 output and the second half from the read 2 output, but the bytes can be swapped. This was probably used to read an aligned 16-bit word if it was unaligned in memory.

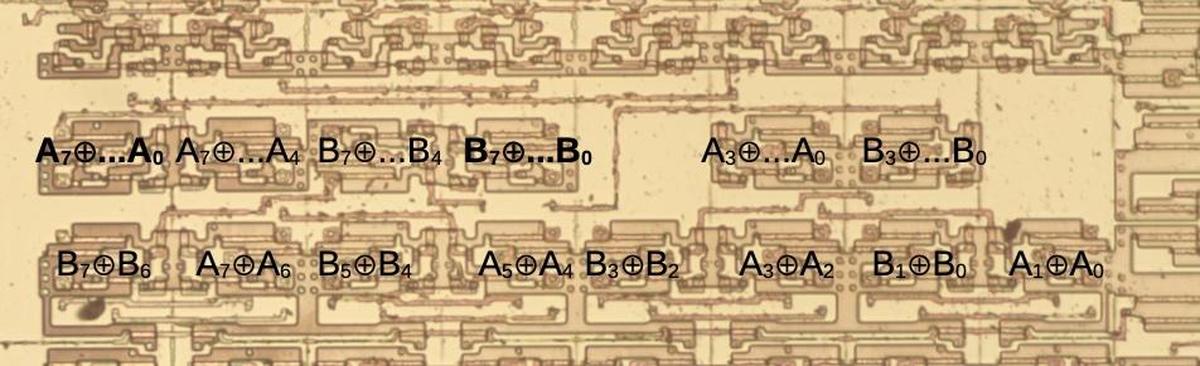

Parity circuits

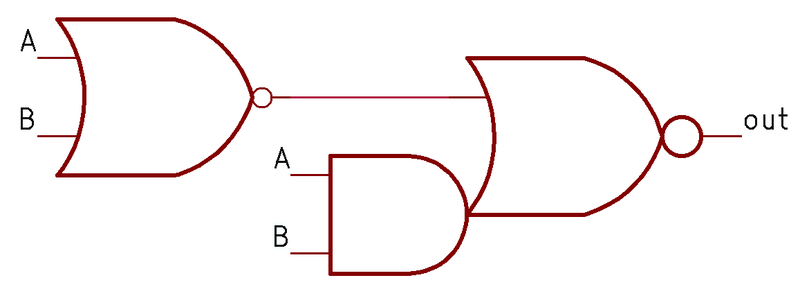

In the lower right part of the chip are two parity circuits, each computing the parity of an 8-bit input. The parity of an input is computed by XORing the bits together through a tree of 2-input XOR gates. First, four gates process pairs of input bits. Next, two XOR gates combine the outputs of the first gates. Finally, an XOR gate combines the two previous outputs to generate the final parity.

The schematic below shows how an XOR gate is built from a NOR gate and an AND-NOR gate. If both inputs are 0, the first NOR gate forces the output to 0. If both inputs are 1, the AND gate forces the output to 0. Thus, the circuit computes XOR. Each labeled block above implements the XOR circuit below.

Conclusion

My conclusion is that the processor for the Keystone II board is probably one of the other chips, one of the IBM metal-can MST packages, and this chip helps with data movement in some way. It would be possible to trace out the complete circuitry of the chip and determine exactly how it functions, but that is too time-consuming a project for this relatively obscure chip.

Follow me on Twitter @kenshirriff or RSS for more chip posts. I'm also on Mastodon occasionally as @[email protected]. Thanks to Al Kossow for providing the chip and Dag Spicer for providing photos. Thanks to Eric Schlaepfer for discussion.

Notes and references

-

The 3274 Control Unit was replaced by the 3174 Establishment Controller, introduced in 1986. An "Establishment Controller" managed a cluster of peripherals or PCs connected to a host mainframe, essentially a box that provided a "kitchen-sink" of functionality including terminal support, local disk storage, Ethernet or token-ring networking, ASCII terminal support, encryption/decryption, and modem support. These units ranged from PC-sized boxes to mini-fridge-sized boxes, depending on how much functionality was required. ↩

-

I'm serious that my laptop can barely handle one person; my 2017 MacBook Air starts dropping characters if it has even a moderate load, and I have to start one-finger typing. You would think that a 1.8 GHz dual-core i5 processor could handle more than 2 characters per second. I don't know if there's something wrong with it, or if modern software just has too much overhead. Don't worry, I upgraded and do most of my work on a faster, more recent laptop. ↩

-

The IBM hardware model had the CPU focusing on the big picture, while the hierarchy of boxes underneath processed data, performed storage, handled printing, and so forth. In a sense, this paralleled the structure of offices in that era, where executives had assistants and secretaries to do the tedious work for them: typing, filing, and so forth. Nowadays, the computer hierarchy and the office hierarchy are both considerably flatter. Maybe there's a connection? ↩

-

A ROM and a PLA are similar in many ways. The general distinction is that a ROM activates one word (row) at a time, while a PLA can activate multiple rows at a time and combine the values, giving more flexibility. A ROM generally has a binary decoder to select the row. This decoder can be recognized by its binary structure: transistors alternating by 1's, by 2's, by 4's, and so forth. ↩

![The Keystone II board. The box is labeled Keystone II FCS [i.e. First Customer Shipment] July 23, 1982. Photo from bitsavers, originally from Bob Roberts. The Keystone II board. The box is labeled Keystone II FCS [i.e. First Customer Shipment] July 23, 1982. Photo from bitsavers, originally from Bob Roberts.](https://static.righto.com/images/ibm-3274/keystone-ii-w600.jpg)

11 comments:

If you ever want to get a bunch of ancient neckbeards monologing, just ask what the difference is between 'enter' and 'return'. Ho boy!

If only intel persevered with the iAPX_432 architecture, we'd have proper computers today, not all thess barely-working x86 heaps. My hopes are on RISC-V, maybe that can save us. Who am I kidding, it will be ARM.

In 1990 I went to a course on programming for business environments (on mainframes obviously).

I can't remember much detail about it, but it focused on techniques for dealing with a 3270 terminal environment, and they called it "pseudo-interactive" programming.

Ken,

I worked my whole life at IBM Brasil, in the maintenance area on all types of equipment (including Mainframes, PSeries, etc.). For many years I maintained the IBM 3274. Thank you for sharing so much technical information that at the time, we did not have access to. The manuals helped with maintenance, but the diagrams were in blocks.

Gustavo Murta

I believe the following used the IBM Universal Controller Processor architecture UC.x

IBM 8100 (UC.1)

IBM 3274

IBM 3081 (service processor)

IBM 3683 & 3684 (checkout counter)

The UC.1 hardware instruction architecture in the 8100 distributive system shown above had some strange hardware instructions. The Load Half Word and Short (LHS) instruction was always difficult to explain. The disable/enable all hardware interrupts was my favorite instruction. The rule was not to disable for more than 75 hardware instructions.

Excellent article as usual - you've got to be an alien! For terminology we use card > board > gate > frame. So this would have been a Keystone II "card", plugged into a board (nitpicky but the IBM guys would slap you silly). The blue/white components are resistor packs while black and orange are typically capacitors (mostly from Kemet). Lots of IBM documentation on Al Kossow's site https://bitsavers.org/pdf/ibm/3274/ There's even a nice cross-reference between IBM's VTL (vendor-transistor-logic) and standard TTL; https://bitsavers.org/pdf/ibm/logic/IC_Cross-Reference/ Fun stuff.

I spent several years writing minicomputer software to drive Honeywell VIP terminals that were similar to IBM. It seemed to me that the terminal design had evolved from older designs without processors where all functions were controlled or triggered by special (non-printing) characters or multi-character escape sequences. I bet the numerous PLA blocks and 16x16 memory were related to recognizing the control sequences. The lack of an adder or counter also seems consistent with dedicated hardware to recognize embedded control sequences. By the time this IBM terminal was designed, I think more sophisticated terminal control was possible, but the older approach was kept for compatibility -- always a holy grail. Keep up the good work -- it's always fascinating.

Control Unit Model 61C Maintenance Information lists this:

Control Logic + 64K Vol 0

Control Logic (Location E2). This card contains an interrupt-driven processor that controls the I/O devices such as the disk file and the host attachment adapters. The first two programs containing IML diagnostics are stored in ROS while the remaining diagnostics and operational code are loaded from the diskette and are stored in RAM on this card. Also contained on the Control Logic card is RAM Storage Volume 8 (64K bytes). The other volumes of storage are control led from the Control Logic card.

Great work as usual Ken. I've always viewed IBM as 'alien' technology due to their unique construction and the difficulty in getting the technical documentation. I'd be interested in knowing more about how their engineers went about designing the boards. For some bizarre reason, I have this idea in my head to build an emulation of the System 38. Problem is that information seems thin on the ground and getting access to the required doc and hardware in order to extract code even thinner. For those not aware of the System 38, it was a departure from the 'normal' ways of computing. Whilst it morphed into the AS/400 and iSeries, the Sys38 marks the change in direction in terms of the database as part of the o/s, single level store (disk was viewed as a virtual memory space) and everything is an object.

Both IBM and AT&T/Bell Labs often seemed to use "oddball" component, board and packaging designs that differed from industry standard norms. I think this was because they frequently were the first to use a new component in volume. They also had the money to do it their own way (and a lot of pride). Companies coming later didn't have the volume for custom everything but could use "industry standard" components that eventually emerged.

I worked in IBM customer support for some IBM 8100 software in the early 1980's. The hardware was UC.1, which was an extension of the hardware used for communication controllers (UC.5) if I remember correctly. Coming from the IBM 370 systems, the 8100 instruction set was well, weird.

Post a Comment