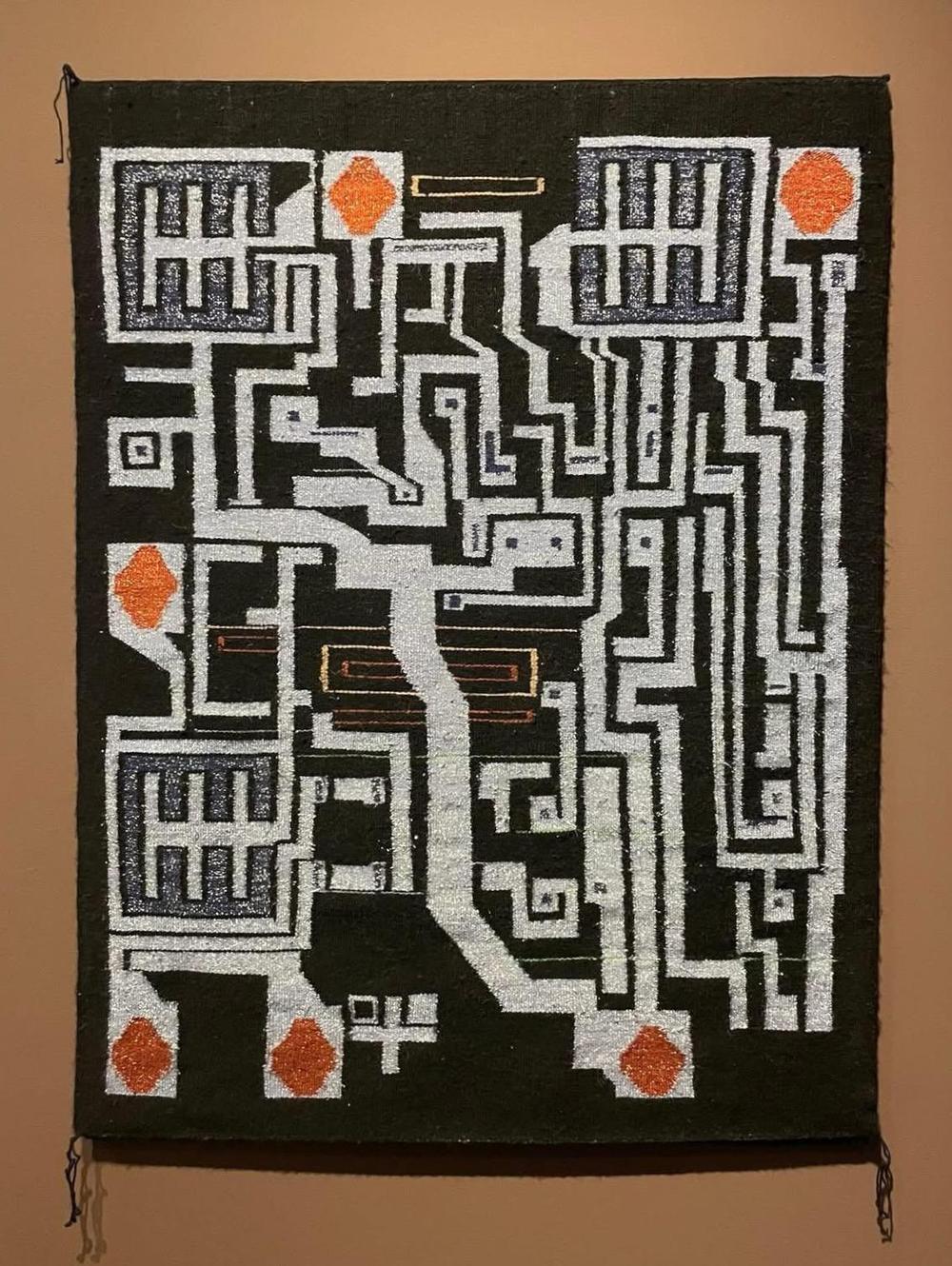

The noted Diné (Navajo) weaver Marilou Schultz recently completed an intricate weaving composed of thick white lines on a black background, punctuated with reddish-orange diamonds. Although this striking rug may appear abstract, it shows the internal circuitry of a tiny silicon chip known as the 555 timer. This chip has hundreds of applications in everything from a sound generator to a windshield wiper controller. At one point, the 555 was the world's best-selling integrated circuit with billions sold. But how did the chip get turned into a rug?

The 555 chip is constructed from a tiny flake of silicon with a layer of metallic wiring on top. In the rug, this wiring is visible as the thick white lines, while the silicon forms the black background. One conspicuous feature of the rug is the reddish-orange diamonds around the perimeter. These correspond to the connections between the silicon chip and its eight pins. Tiny golden bond wires—thinner than a human hair—are attached to the square bond pads to provide these connections. The circuitry of the 555 chip contains 25 transistors, silicon devices that can switch on and off. The rug is dominated by three large transistors, the filled squares with a 王 pattern inside, while the remaining transistors are represented by small dots.

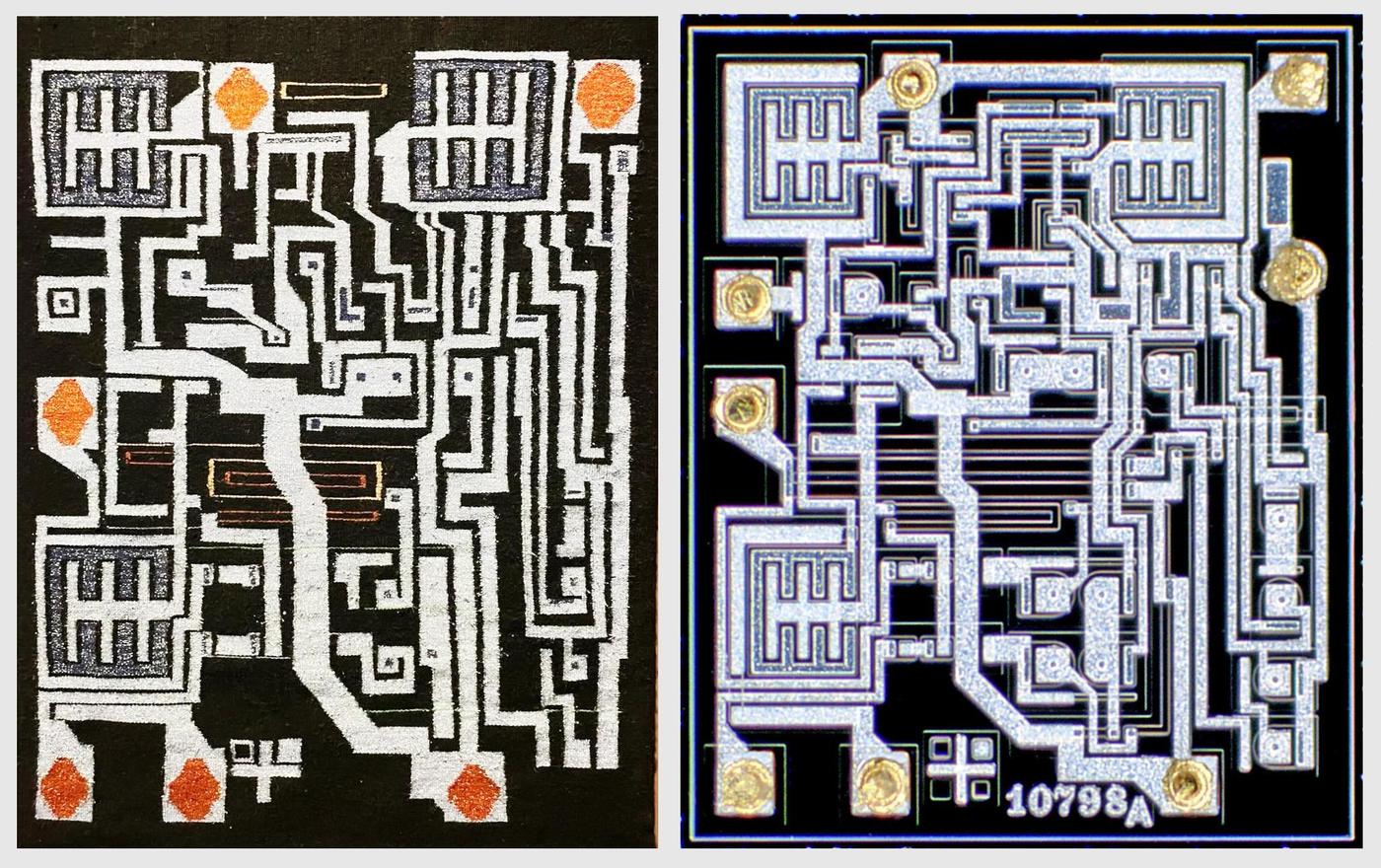

The weaving was inspired by a photo of the 555 timer die taken by Antoine Bercovici (Siliconinsider); I suggested this photo to Schultz as a possible subject for a rug. The diagram below compares the weaving (left) with the die photo (right). As you can see, the weaving closely follows the actual chip, but there are a few artistic differences. For instance, two of the bond pads have been removed, the circuitry at the top has been simplified, and the part number at the bottom has been removed.

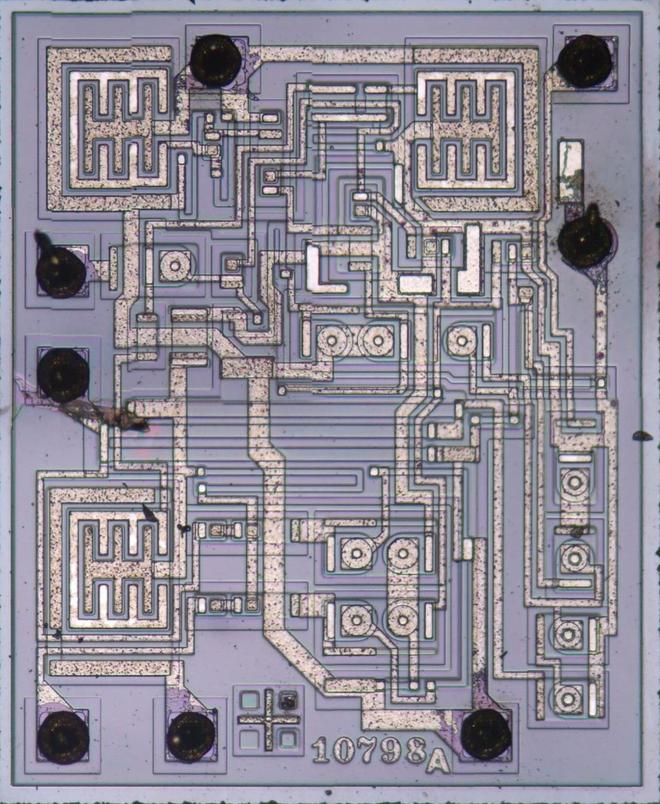

Antoine took the die photo with a dark field microscope, a special type of microscope that produces an image on a black background. This image emphasizes the metal layer on the top of the die. In comparison, a standard bright-field microscope produced the image below. When a chip is manufactured, regions of silicon are "doped" with impurities to create transistors and resistors. These regions are visible in the image below as subtle changes in the color of the silicon.

In the weaving, the chip's design appears almost monumental, making it easy to forget that the actual chip is microscopic. For the photo below, I obtained a version of the chip packaged in a metal can, rather than the typical rectangle of black plastic. Cutting the top off the metal can reveals the tiny chip inside, with eight gold bond wires connecting the die to the pins of the package. If you zoom in on the photo, you may recognize the three large transistors that dominate the rug.

The artist, Marilou Schultz, has been creating chip rugs since 1994, when Intel commissioned a rug based on the Pentium as a gift to AISES (American Indian Science & Engineering Society). Although Schultz learned weaving as a child, the Pentium rug was a challenge due to its complex pattern and lack of symmetry; a day's work might add just an inch to the rug. This dramatic weaving was created with wool from the long-horned Navajo-Churro sheep, colored with traditional plant dyes.

For the 555 timer weaving, Schultz experimented with different materials. Silver and gold metallic threads represent the aluminum and copper in the chip. The artist explains that "it took a lot more time to incorporate the metallic threads," but it was worth the effort because "it is spectacular to see the rug with the metallics in the dark with a little light hitting it." Aniline dyes provided the black and lavender colors. Although natural logwood dye produces a beautiful purple, it fades over time, so Schultz used an aniline dye instead. The lavender colors are dedicated to the weaver's mother, who passed away in February; purple was her favorite color.

Inside the chip

How does the 555 chip produce a particular time delay? You add external components—resistors and a capacitor—to select the time. The capacitor is filled (charged) at a speed controlled by the resistor. When the capacitor get "full", the 555 chip switches operation and starts emptying (discharging) the capacitor. It's like filling a sink: if you have a large sink (capacitor) and a trickle of water (large resistor), the sink fills slowly. But if you have a small sink (capacitor) and a lot of water (small resistor), the sink fills quickly. By using different resistors and capacitors, the 555 timer can provide time intervals from microseconds to hours.

I've constructed an interactive chip browser that shows how the regions of the rug correspond to specific electronic components in the physical chip. Click on any part of the rug to learn the function of the corresponding component in the chip.

For instance, two of the large square transistors turn the chip's output on or off, while the third large transistor discharges the capacitor when it is full. (To be precise, the capacitor goes between 1/3 full and 2/3 full to avoid issues near "empty" and "full".) The chip has circuits called comparators that detect when the capacitor's voltage reaches 1/3 or 2/3, switching between emptying and filling at those points. If you want more technical details about the 555 chip, see my previous articles: an early 555 chip, a 555 timer similar to the rug, and a more modern CMOS version of the 555.

Conclusions

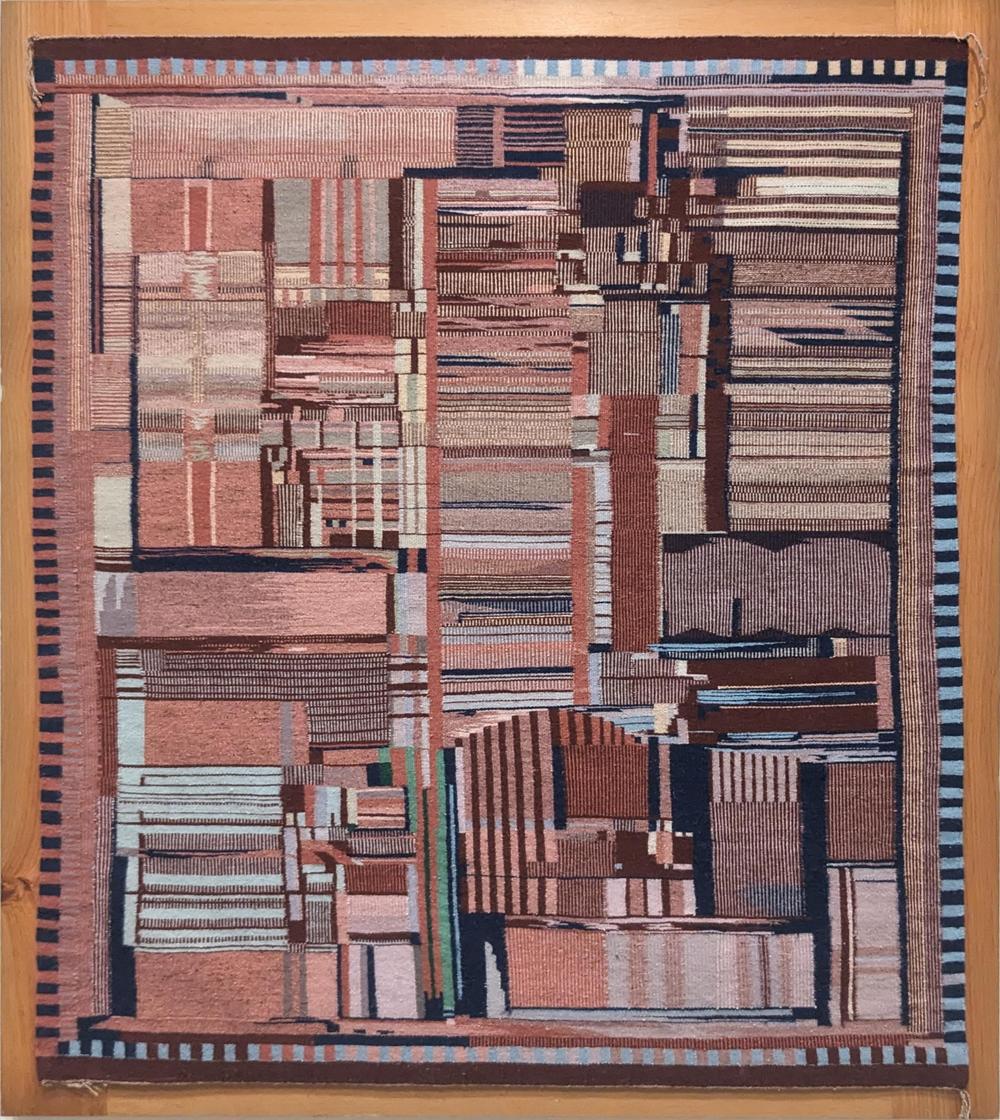

The similarities between Navajo weavings and the patterns in integrated circuits have long been recognized. Marilou Schultz's weavings of integrated circuits make these visual metaphors into concrete works of art. This connection is not just metaphorical, however; in the 1960s, the semiconductor company Fairchild employed numerous Navajo workers to assemble chips in Shiprock, New Mexico. I wrote about this complicated history in The Pentium as a Navajo Weaving.

This work is being shown at SITE Santa Fe's Once Within a Time exhibition (running until January 2026). I haven't seen the exhibition in person, so let me know if you visit it. For more about Marilou Schultz's art, see The Diné Weaver Who Turns Microchips Into Art, or A Conversation with Marilou Schultz on YouTube.

Many thanks to Marilou Schultz for discussing her art with me. Thanks to First American Art Magazine for providing the photo of her 555 rug. Follow me on Mastodon (@[email protected]), Bluesky (@righto.com), or RSS for updates.