In the 1980s, if you wanted your computer to do floating-point calculations faster, you could buy the Intel 8087 floating-point coprocessor chip. Plugging it into your IBM PC would make operations up to 100 times faster, a big boost for spreadsheets and other number-crunching applications. The 8087 uses complicated algorithms to compute trigonometric, logarithmic, and exponential functions. These algorithms are implemented inside the chip in microcode. I'm part of a group that is reverse-engineering this microcode. In this post, I examine the 49 types of conditional tests that the 8087's microcode uses inside its algorithms. Some conditions are simple, such as checking if a number is zero or negative, while others are specialized, such as determining what direction to round a number.

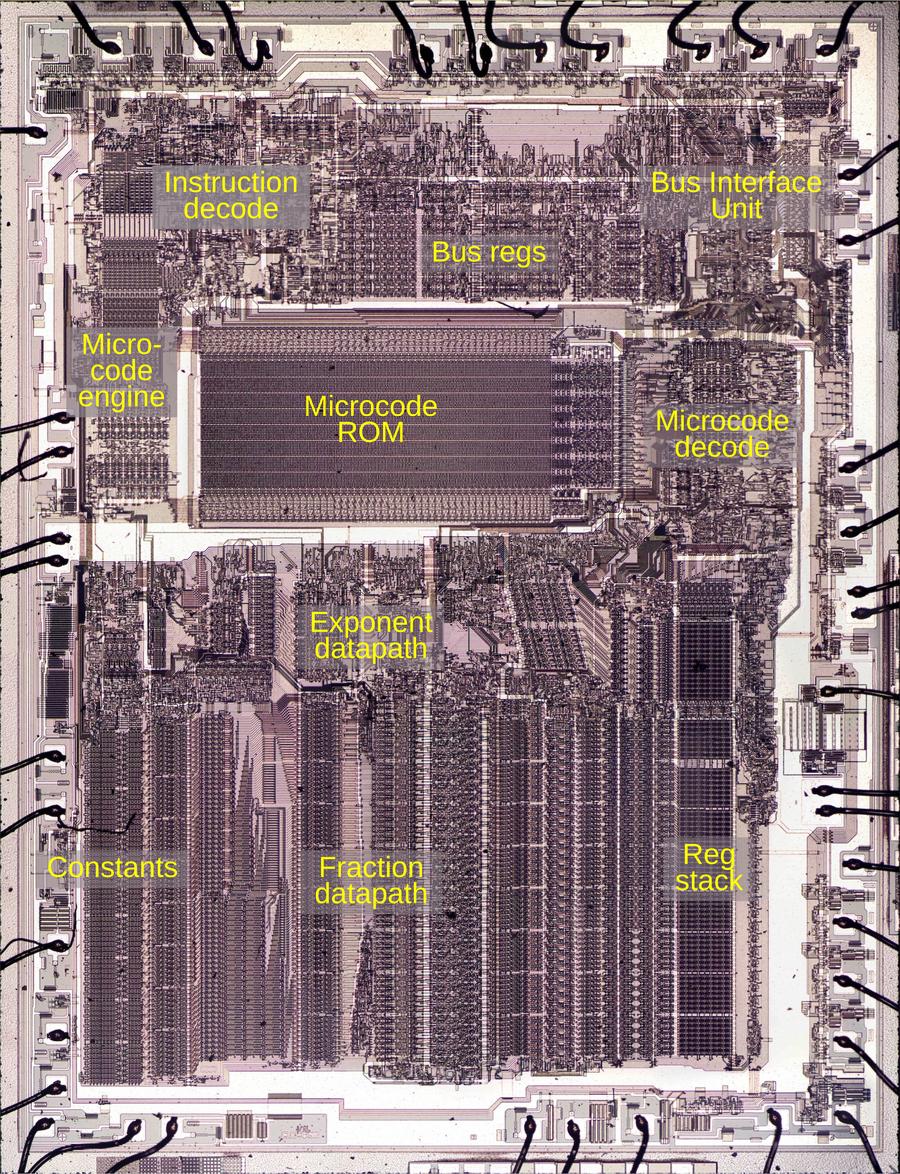

To explore the 8087's circuitry, I opened up an 8087 chip and took numerous photos of the silicon die with a microscope. Around the edges of the die, you can see the hair-thin bond wires that connect the chip to its 40 external pins. The complex patterns on the die are formed by its metal wiring, as well as the polysilicon and silicon underneath. The bottom half of the chip is the "datapath", the circuitry that performs calculations on 80-bit floating point values. At the left of the datapath, a constant ROM holds important constants such as π. At the right are the eight registers that the programmer uses to hold floating-point values; in an unusual design decision, these registers are arranged as a stack.

The chip's instructions are defined by the large microcode ROM in the middle. To execute a floating-point instruction, the 8087 decodes the instruction and the microcode engine starts executing the appropriate micro-instructions from the microcode ROM. The microcode decode circuitry to the right of the ROM generates the appropriate control signals from each micro-instruction.1 The bus registers and control circuitry handle interactions with the main 8086 processor and the rest of the system.

The 8087's microcode

Executing an 8087 instruction such as arctan requires hundreds of internal steps to compute the result. These steps are implemented in microcode with micro-instructions specifying each step of the algorithm. (Keep in mind the difference between the assembly language instructions used by a programmer and the undocumented low-level micro-instructions used internally by the chip.) The microcode ROM holds 1648 micro-instructions, implementing the 8087's instruction set. Each micro-instruction is 16 bits long and performs a simple operation such as moving data inside the chip, adding two values, or shifting data. I'm working with the "Opcode Collective" to reverse engineer the micro-instructions and fully understand the microcode (link).

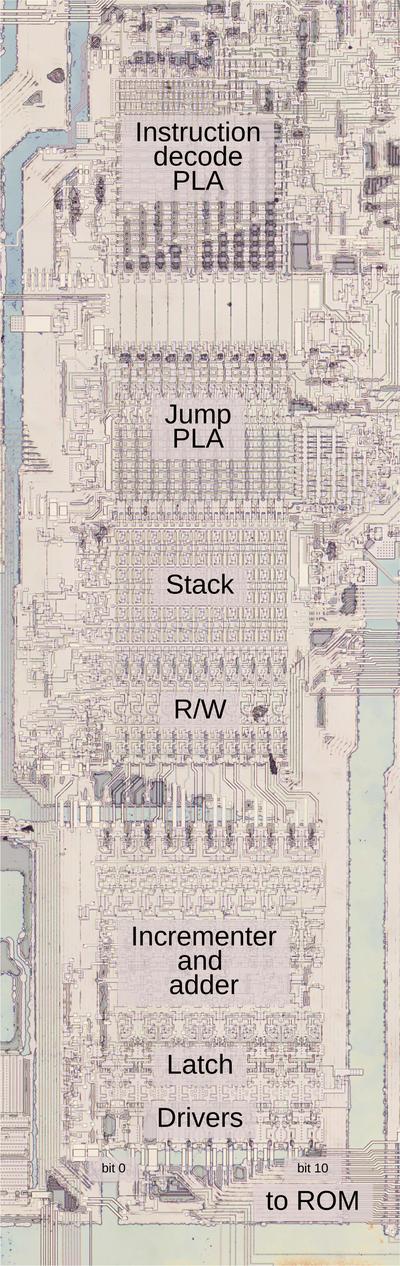

The microcode engine (below) controls the execution of micro-instructions, acting as the mini-CPU inside the 8087. Specifically, it generates an 11-bit micro-address, the address of a micro-instruction in the ROM. The microcode engine implements jumps, subroutine calls, and returns within the microcode. These jumps, subroutine calls, and returns are all conditional; the microcode engine will either perform the operation or skip it, depending on the value of a specified condition.

I'll write more about the microcode engine later, but I'll give an overview here. At the top, the Instruction Decode PLA2 decodes an 8087 instruction to determine the starting address in microcode. Below that, the Jump PLA holds microcode addresses for jumps and subroutine calls. Below this, six 11-bit registers implement the microcode stack, allowing six levels of subroutine calls inside the microcode. (Note that this stack is completely different from the 8087's register stack that holds eight floating-point values.) The stack registers have associated read/write circuitry. The incrementer adds one to the micro-address to step through the code. The engine also implements relative jumps, using an adder to add an offset to the current location. At the bottom, the address latch and drivers boost the 11-bit address output and send it to the microcode ROM.

Selecting a condition

A micro-instruction can say "jump ahead 5 micro-instructions if a register is zero" and the microcode engine will either perform the jump or ignore it, based on the register value. In the circuitry, the condition causes the microcode engine to either perform the jump or block the jump. But how does the hardware select one condition out of the large set of conditions?

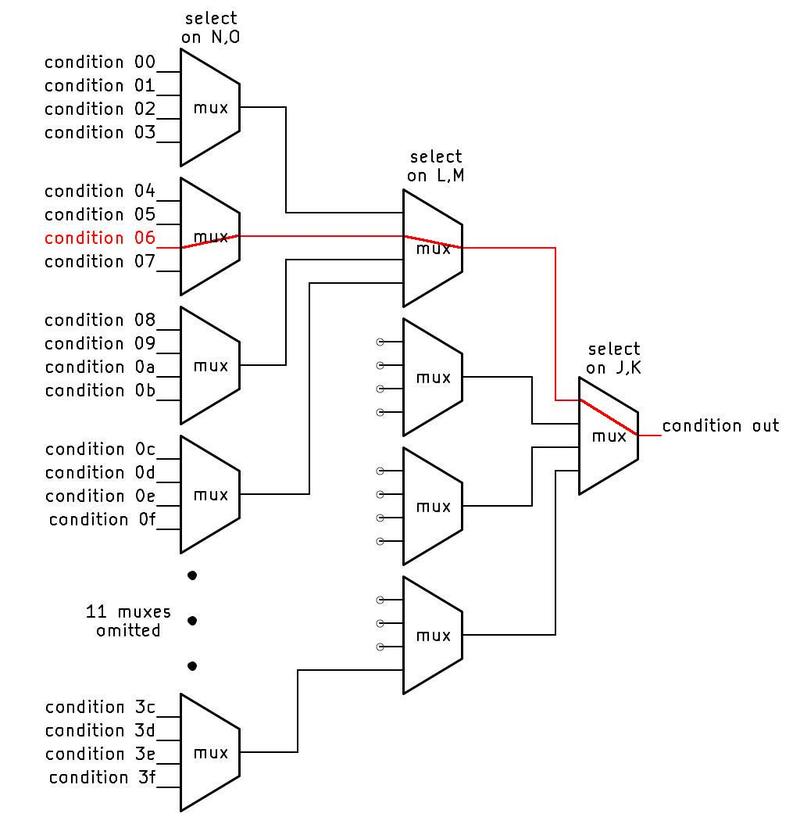

Six bits of the micro-instruction can specify one of 64 conditions. A circuit similar to the idealized diagram below selects the specified condition. The key component is a multiplexer, represented by a trapezoid below. A multiplexer is a simple circuit that selects one of its four inputs. By arranging multiplexers in a tree, one of the 64 conditions on the left is selected and becomes the output, passed to the microcode engine.

For example, if bits J and K of the microcode are 00, the rightmost multiplexer will select the first input. If bits LM are 01, the middle multiplexer will select the second input, and if bits NO are 10, the left multiplexer will select its third input. The result is that condition 06 will pass through the tree and become the output.3 By changing the bits that control the multiplexers, any of the inputs can be used. (We've arbitrarily given the 16 microcode bits the letter names A through P.)

Physically, the conditions come from locations scattered across the die. For instance, conditions involving the opcode come from the instruction decoding part of the chip, while conditions involving a register are evaluated next to the register. It would be inefficient to run 64 wires for all the conditions to the microcode engine. The tree-based approach reduces the wiring since the "leaf" multiplexers can be located near the associated condition circuitry. Thus, only one wire needs to travel a long distance rather than multiple wires. In other words, the condition selection circuitry is distributed across the chip instead of being implemented as a centralized module.

Because the conditions don't always fall into groups of four, the actual implementation is slightly different from the idealized diagram above. In particular, the top-level multiplexer has five inputs, rather than four.4 Other multiplexers don't use all four inputs. This provides a better match between the physical locations of the condition circuits and the multiplexers. In total, 49 of the possible 64 conditions are implemented in the 8087.

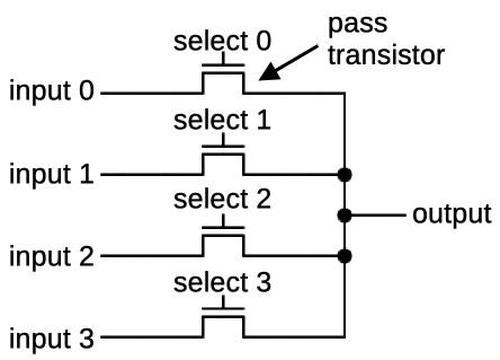

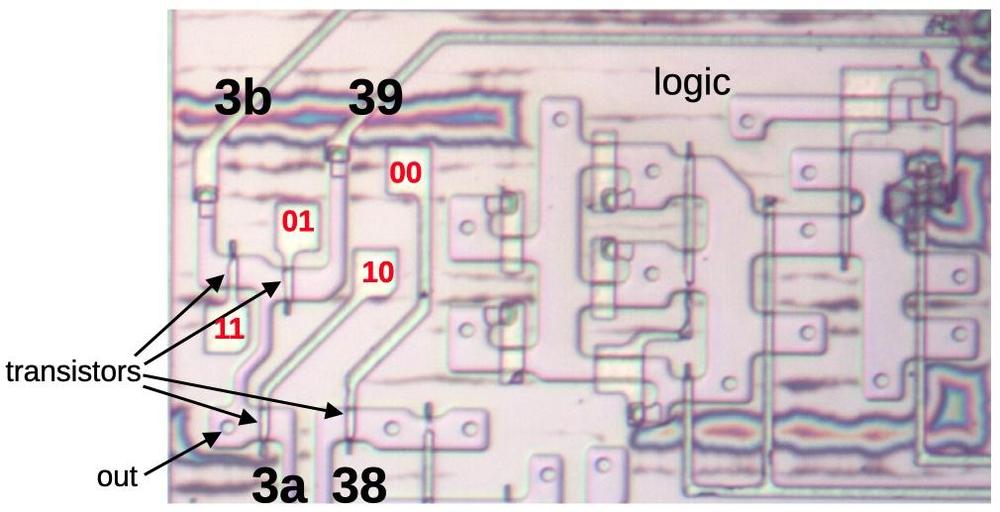

The circuit that selects one of the four conditions is called a multiplexer. It is constructed from pass transistors, transistors that are configured to either pass a signal through or block it. To operate the multiplexer, one of the select lines is energized, turning on the corresponding pass transistor. This allows the selected input to pass through the transistor to the output, while the other inputs are blocked.

The diagram below shows how a multiplexer appears on the die. The pinkish regions are doped silicon. The white lines are polysilicon wires. When polysilicon crosses over doped silicon, a transistor is formed. On the left is a four-way multiplexer, constructed from four pass transistors. It takes inputs (black) for four conditions, numbered 38, 39, 3a, and 3b. There are four control signals (red) corresponding to the four combinations of bits N and O. One of the inputs will pass through a transistor to the output, selected by the active control signal. The right half contains the logic (four NOR gates and two inverters) to generate the control signals from the microcode bits. (Metal lines run horizontally from the logic to the control signal contacts, but I dissolved the metal for this photo.) Each multiplexer in the 8087 has a completely different layout, manually optimized based on the location of the signals and surrounding circuitry. Although the circuit for a multiplexer is regular (four transistors in parallel), the physical layout looks somewhat chaotic.

The 8087 uses pass transistors for many circuits, not just multiplexers. Circuits with pass transistors are different from regular logic gates because the pass transistors provide no amplification. Instead, signals get weaker as they go through pass transistors. To solve this problem, inverters or buffers are inserted into the condition tree to boost signals; they are omitted from the diagram above.

The conditions

Of the 8087's 49 different conditions, some are widely used in the microcode, while others are designed for a specific purpose and are only used once. The full set of conditions is described in a footnote7 but I'll give some highlights here.

Fifteen conditions examine the bits of the current instruction's opcode. This allows one microcode routine to handle a group of similar instructions and then change behavior based on the specific instruction. For example, conditions test if the instruction is multiplication, if the instruction is an FILD/FIST (integer load or store), or if the bottom bit of the opcode is set.5

The 8087 has three temporary registers—tmpA, tmpB, and tmpC—that hold values during computation. Various conditions examine the values in the tmpA and tmpB registers.6 In particular, the 8087 uses an interesting way to store numbers internally: each 80-bit floating-point value also has two "tag" bits. These bits are mostly invisible to the programmer and can be thought of as metadata. The tag bits indicate if a register is empty, contains zero, contains a "normal" number, or contains a special value such as NaN (Not a Number) or infinity. The 8087 uses the tag bits to optimize operations. The tags also detect stack overflow (storing to a non-empty stack register) or stack underflow (reading from an empty stack register).

Other conditions are highly specialized. For instance, one condition looks at the rounding mode setting and the sign of the value to determine if the value should be rounded up or down. Other conditions deal with exceptions such as numbers that are too small (i.e. denormalized) or numbers that lose precision. Another condition tests if two values have the same sign or not. Yet another condition tests if two values have the same sign or not, but inverts the result if the current instruction is subtraction. The simplest condition is simply "true", allowing an unconditional branch.

For flexibility, conditions can be "flipped", either jumping if the condition is true or jumping if the condition is false. This is controlled by bit P of the microcode. In the circuitry, this is implemented by a gate that XORs the P bit with the condition. The result is that the state of the condition is flipped if bit P is set.

For a concrete example of how conditions are used, consider the

microcode routine

that implements FCHS and FABS, the

instructions to change the sign and compute the absolute value, respectively.

These operations are almost the same (toggling the sign bit versus clearing the sign bit), so the same

microcode routine handles both instructions, with a jump instruction to handle the difference.

The FABS and FCHS instructions were designed with identical opcodes,

except that the bottom bit is set for FABS.

Thus, the microcode routine uses a condition that tests the bottom bit, allowing the routine to branch and

change its behavior for FABS vs FCHS.

Looking at the relevant micro-instruction, it has the hex value

0xc094, or in binary 110 000001 001010 0.

The first three bits (ABC=110) specify the relative jump operation (100 would jump to a fixed target and 101 would

perform a subroutine call.)

Bits D through I (000010) indicate the amount of the jump (+`).

Bits J through O (001010, hex 0a) specify the condition to test, in this case, the last bit of the instruction opcode.

The final bit (P) would toggle the condition if set, (i.e. jump if false).

Thus, for FABS, the jump instruction will jump ahead one micro-instruction.

This has the effect of skipping the next micro-instruction, which sets the appropriate sign bit for

FCHS.

Conclusions

The 8087 performs floating-point operations much faster than the 8086 by using special hardware, optimized for floating-point. The condition code circuitry is one example of this: the 8087 can test a complicated condition in a single operation. However, these complicated conditions make it much harder to understand the microcode. But by a combination of examining the circuitry and looking at the micocode, we're making progress. Thanks to the members of the "Opcode Collective" for their hard work, especially Smartest Blob and Gloriouscow.

For updates, follow me on Bluesky (@righto.com), Mastodon (@[email protected]), or RSS.

Notes and references

-

The section of the die that I've labeled "Microcode decode" performs some of the microcode decoding, but large parts of the decoding are scattered across the chip, close to the circuitry that needs the signals. This makes reverse-engineering the microcode much more difficult. I thought that understanding the microcode would be straightforward, just examining a block of decode circuitry. But this project turned out to be much more complicated and I need to reverse-engineer the entire chip. ↩

-

A PLA is a "Programmable Logic Array". It is a technique to implement logic functions with grids of transistors. A PLA can be used as a compressed ROM, holding data in a more compact representation. (Saving space was very important in chips of this era.) In the 8087, PLAs are used to hold tables of microcode addresses. ↩

-

Note that the multiplexer circuit selects the condition corresponding to the binary value of the bits. In the example, bits 000110 (0x06) select condition 06. ↩

-

The five top-level multiplexer inputs correspond to bit patterns 00, 011, 10, 110, and 111. That is, two inputs depend on bits J and K, while three inputs depend on bits J, K, and L. The bit pattern 010 is unused, corresponding to conditions 0x10 through 0x17, which aren't implemented. ↩

-

The 8087 acts as a co-processor with the 8086 processor. The 8086 instruction set is designed so instructions with a special "ESCAPE" sequence in the top 5 bits are processed by the co-processor, in this case the 8087. Thus, the 8087 receives a 16-bit instruction, but only the bottom 11 bits are usable. For a memory operation, the second byte of the instruction is an 8086-style ModR/M byte. For instructions that don't access memory, the second byte specifies more of the instruction and sometimes specifies the stack register to use for the instruction.

The relevance of this is that the 8087's microcode engine uses the 11 bits of the instruction to determine which microcode routine to execute. The microcode also uses various condition codes to change behavior depending on different bits of the instruction. ↩

-

There is a complication with the tmpA and tmpB registers: they can be swapped with the micro-instruction "ABC.EF". The motivation behind this is that if you have two arguments, you can use a micro-subroutine to load an argument into tmpA, swap the registers, and then use the same subroutine to load the second argument into tmpA. The result is that the two arguments end up in tmpB and tmpA without any special coding in the subroutine.

The implementation doesn't physically swap the registers, but renames them internally, which is much more efficient. A flip-flop is toggled every time the registers are swapped. If the flip-flop is set, a request goes to one register, while if the flip-flop is clear, a request goes to the other register. (Many processors use the same trick. For instance, the Intel 8080 has an instruction to exchange the DE and HL registers. The Z80 has an instruction to swap register banks. In both cases, a flip-flop renames the registers, so the data doesn't need to move.) ↩

-

The table below is the real meat of this post, the result of much circuit analysis. These details probably aren't interesting to most people, so I've relegated the table to a footnote. Descriptions in italics are provided by Smartest Blob based on examination of the microcode. Grayed-out lines are unused conditions.

The table has five sections, corresponding to the 5 inputs to the top-level condition multiplexer. These inputs come from different parts of the chip, so the sections correspond to different categories of conditions.

The first section consists of instruction parsing, with circuitry near the microcode engine. The description shows the 11-bit opcode pattern that triggers the condition, with 0 bits and 1 bits as specified, and X indicating a "don't care" bit that can be 0 or 1. Where simpler, I list the relevant instructions instead.

The next section indicates conditions on the exponent. I am still investigating these conditions, so the descriptions are incomplete. The third section is conditions on the temporary registers or conditions related to the control register. These circuits are to the right of the microcode ROM.

Conditions in the fourth section examine the floating-point bus, with circuitry near the bottom of the chip. Conditions 34 and 35 use a special 16-bit bidirectional shift register, at the far right of the chip. The top bit from the floating-point bus is shifted in. Maybe this shift register is used for CORDIC calculations? The conditions in the final block are miscellaneous, including the always-true condition 3e, which is used for unconditional jumps.

Cond. Description 00 not XXX 11XXXXXX 01 1XX 11XXXXXX 02 0XX 11XXXXXX 03 X0X XXXXXXXX 04 not cond 07 or 1XX XXXXXXXX 05 not FLD/FSTP temp-real or BCD 06 110 xxxxxxxx or 111 xx0xxxxx 07 FLD/FSTP temp-real 08 FBLD/FBSTP 09 0a XXX XXXXXXX1 0b XXX XXXX1XXX 0c FMUL 0d FDIV FDIVR 0e FADD FCOM FCOMP FCOMPP FDIV FDIVR FFREE FLD FMUL FST FSTP FSUB FSUBR FXCH 0f FCOM FCOMP FCOMPP FTST 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 exponent condition 19 exponent condition 1a exponent condition 1b exponent condition 1c exponent condition 1d exponent condition 1e eight exponent zero bits 1f exponent condition 20 tmpA tag ZERO 21 tmpA tag SPECIAL 22 tmpA tag VALID 23 stack overflow 24 tmpB tag ZERO 25 tmpB tag SPECIAL 26 tmpB tag VALID 27 st(i) doesn't exist (A)? 28 tmpA sign 29 tmpB top bit 2a tmpA zero 2b tmpA top bit 2c Control Reg bit 12: infinity control 2d round up/down 2e unmasked interrupt 2f DE (denormalized) interrupt 30 top reg bit 31 32 reg bit 64 33 reg bit 63 34 Shifted top bits, all zero 35 Shifted top bits, one out 36 37 38 const latch zero 39 tmpA vs tmpB sign, flipped for subtraction 3a precision exception 3b tmpA vs tmpB sign 3c 3d 3e unconditional 3f This table is under development and undoubtedly has errors. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment