Early microprocessors were very slow when operating with floating-point numbers. But in 1980, Intel introduced the 8087 floating-point coprocessor, performing floating-point operations up to 100 times faster. This was a huge benefit for IBM PC applications such as AutoCAD, spreadsheets, and flight simulators. The 8087 was so effective that today's computers still use a floating-point system based on the 8087.1

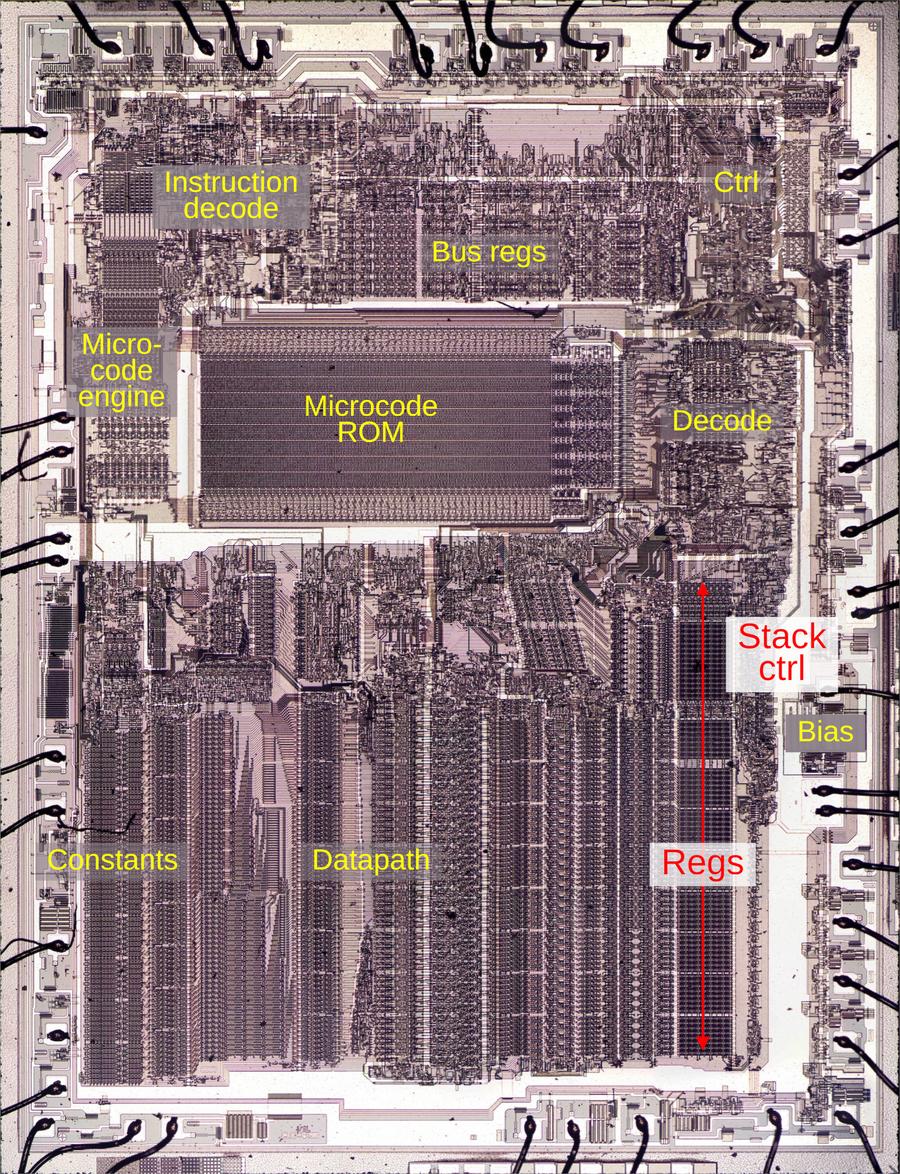

The 8087 was an extremely complex chip for its time, containing somewhere between 40,000 and 75,000 transistors, depending on the source.2 To explore how the 8087 works, I opened up a chip and took numerous photos of the silicon die with a microscope. Around the edges of the die, you can see the hair-thin bond wires that connect the chip to its 40 external pins. The complex patterns on the die are formed by its metal wiring, as well as the polysilicon and silicon underneath. The bottom half of the chip is the "datapath", the circuitry that performs calculations on 80-bit floating point values. At the left of the datapath, a constant ROM holds important constants such as π. At the right are the eight registers that form the stack, along with the stack control circuitry.

The chip's instructions are defined by the large microcode ROM in the middle. This ROM is very unusual; it is semi-analog, storing two bits per transistor by using four transistor sizes. To execute a floating-point instruction, the 8087 decodes the instruction and the microcode engine starts executing the appropriate micro-instructions from the microcode ROM. The decode circuitry to the right of the ROM generates the appropriate control signals from each micro-instruction. The bus registers and control circuitry handle interactions with the main 8086 processor and the rest of the system. Finally, the bias generator uses a charge pump to create a negative voltage to bias the chip's substrate, the underlying silicon.

The stack registers and control circuitry (in red above) are the subject of this blog post. Unlike most processors, the 8087 organizes its registers in a stack, with instructions operating on the top of the stack. For instance, the square root instruction replaces the value on the top of the stack with its square root. You can also access a register relative to the top of the stack, for instance, adding the top value to the value two positions down from the top. The stack-based architecture was intended to improve the instruction set, simplify compiler design, and make function calls more efficient, although it didn't work as well as hoped.

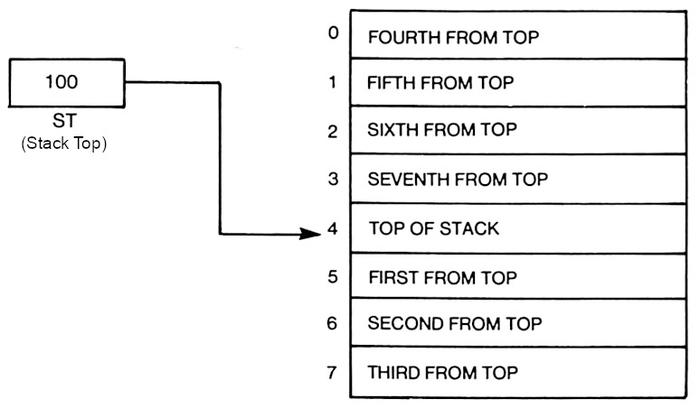

The diagram above shows how the stack operates. The stack consists of eight registers, with the Stack Top (ST) indicating the current top of the stack. To push a floating-point value onto the stack, the Stack Top is decremented and then the value is stored in the new top register. A pop is performed by copying the value from the stack top and then incrementing the Stack Top. In comparison, most processors specify registers directly, so register 2 is always the same register.

The registers

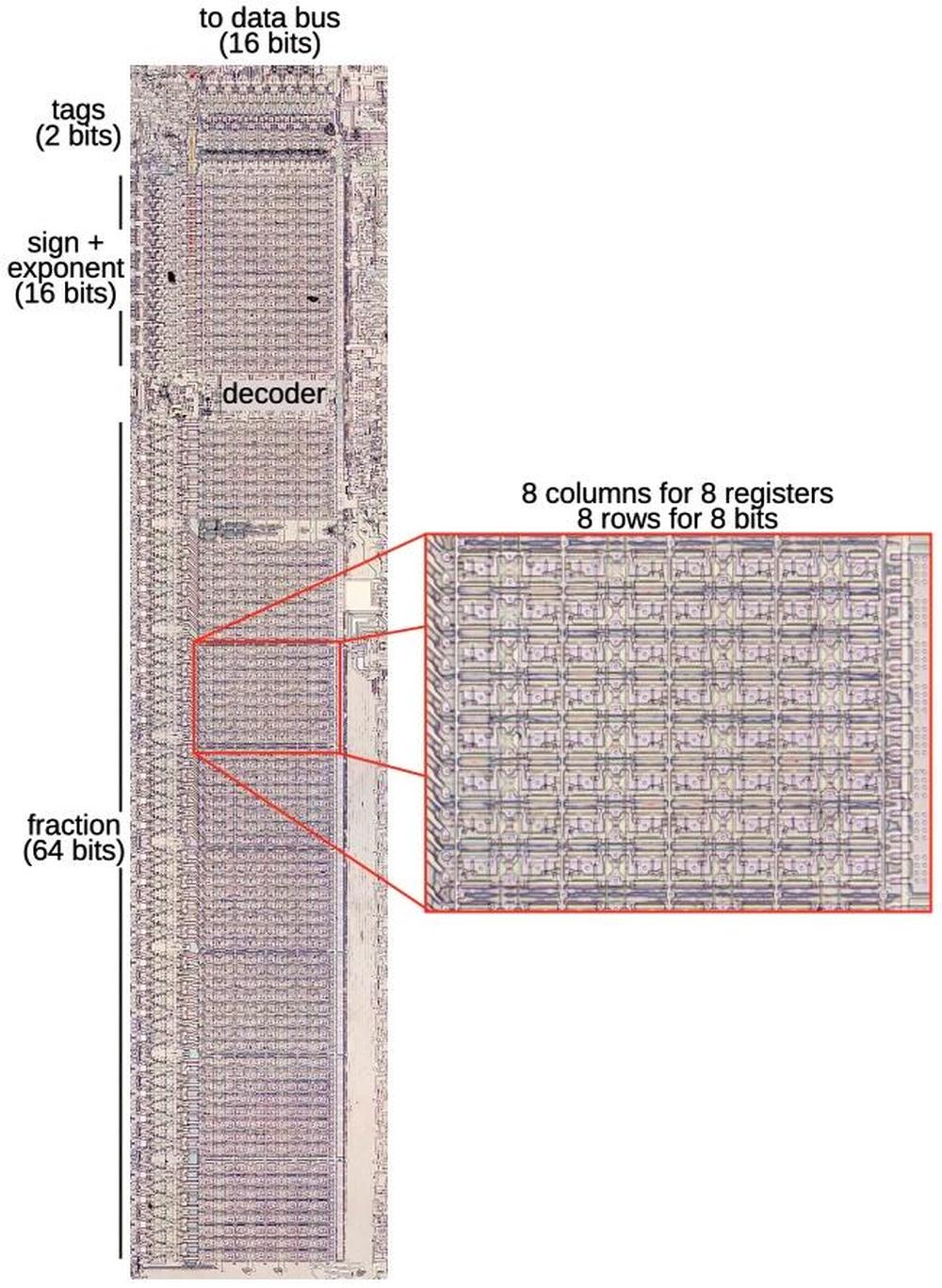

The stack registers occupy a substantial area on the die of the 8087 because floating-point numbers take many bits. A floating-point number consists of a fractional part (sometimes called the mantissa or significand), along with the exponent part; the exponent allows floating-point numbers to cover a range from extremely small to extremely large. In the 8087, floating-point numbers are 80 bits: 64 bits of significand, 15 bits of exponent, and a sign bit. An 80-bit register was very large in the era of 8-bit or 16-bit computers; the eight registers in the 8087 would be equivalent to 40 registers in the 8086 processor.

The registers store each bit in a static RAM cell. Each cell has two inverters connected in a loop. This circuit forms a stable feedback loop, with one inverter on and one inverter off. Depending on which inverter is on, the circuit stores a 0 or a 1. To write a new value into the circuit, one of the lines is pulled low, flipping the loop into the desired state. The trick is that each inverter uses a very weak transistor to pull the output high, so its output is easily overpowered to change the state.

These inverter pairs are arranged in an 8 × 80 grid that implements eight words of 80 bits. Each of the 80 rows has two bitlines that provide access to a bit. The bitlines provide both read and write access to a bit; the pair of bitlines allows either inverter to be pulled low to store the desired bit value. Eight vertical wordlines enable access to one word, one column of 80 bits. Each wordline turns on 160 pass transistors, connecting the bitlines to the inverters in the selected column. Thus, when a wordline is enabled, the bitlines can be used to read or write that word.

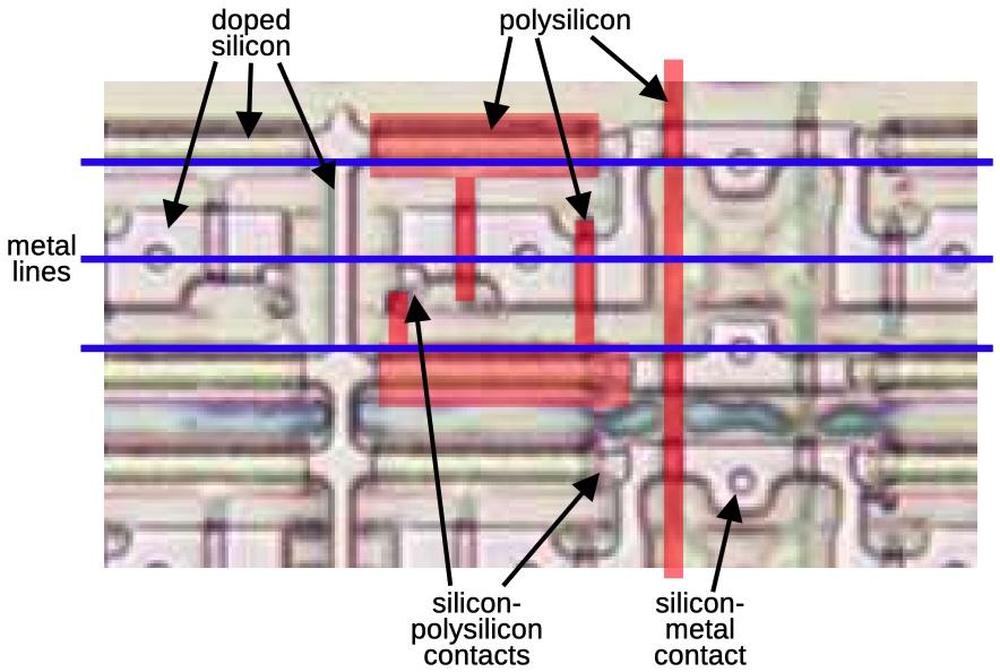

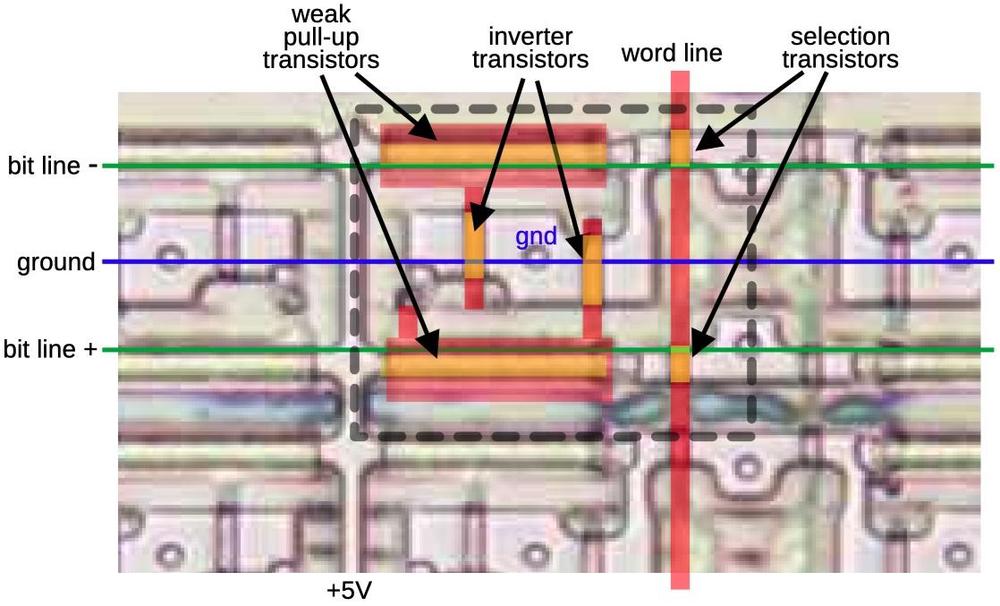

Although the chip looks two-dimensional, it actually consists of multiple layers. The bottom layer is silicon. The pinkish regions below are where the silicon has been "doped" to change its electrical properties, making it an active part of the circuit. The doped silicon forms a grid of horizontal and vertical wiring, with larger doped regions in the middle. On top of the silicon, polysilicon wiring provides two functions. First, it provides a layer of wiring to connect the circuit. But more importantly, when polysilicon crosses doped silicon, it forms a transistor. The polysilicon provides the gate, turning the transistor on and off. In this photo, the polysilicon is barely visible, so I've highlighted part of it in red. Finally, horizontal metal wires provide a third layer of interconnecting wiring. Normally, the metal hides the underlying circuitry, so I removed the metal with acid for this photo. I've drawn blue lines to represent the metal layer. Contacts provide connections between the various layers.

The layers combine to form the inverters and selection transistors of a memory cell, indicated with the dotted line below. There are six transistors (yellow), where polysilicon crosses doped silicon. Each inverter has a transistor that pulls the output low and a weak transistor to pull the output high. When the word line (vertical polysilicon) is active, it connects the selected inverters to the bit lines (horizontal metal) through the two selection transistors. This allows the bit to be read or written.

Each register has two tag bits associated with it, an unusual form of metadata to indicate if the register is empty, contains zero, contains a valid value, or contains a special value such as infinity. The tag bits are used to optimize performance internally and are mostly irrelevant to the programmer. As well as being accessed with a register, the tag bits can be accessed in parallel as a 16-bit "Tag Word". This allows the tags to be saved or loaded as part of the 8087's state, for instance, during interrupt handling.

The decoder

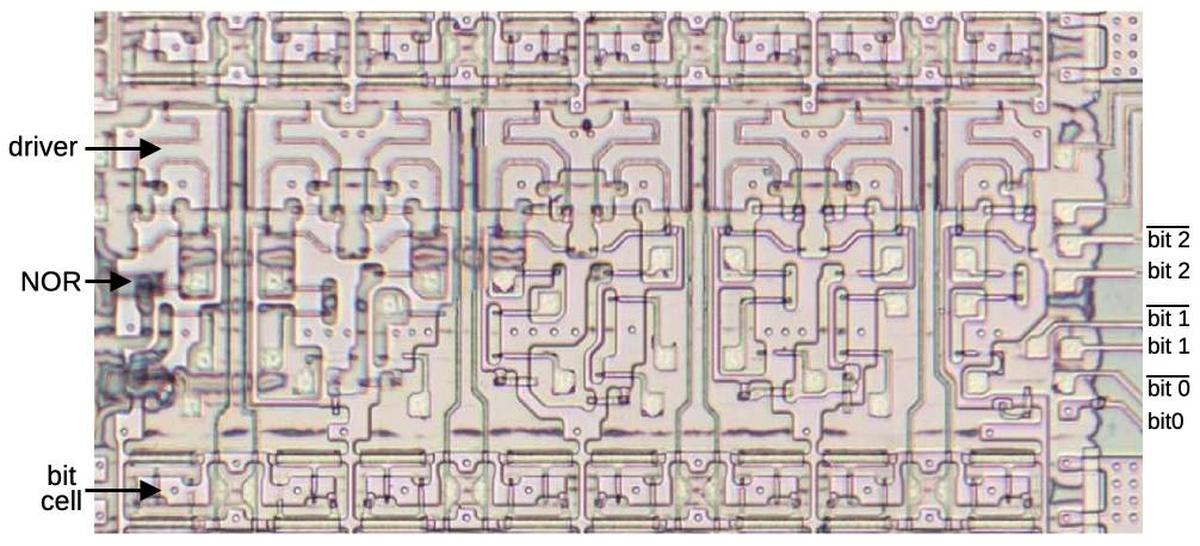

The decoder circuit, wedged into the middle of the register file, selects one of the registers. A register is specified internally with a 3-bit value. The decoder circuit energizes one of the eight register select lines based on this value.

The decoder circuitry is straightforward: it has eight 3-input NOR gates to match one of the eight bit patterns. The select line is then powered through a high-current driver that uses large transistors. (In the photo below, you can compare the large serpentine driver transistors to the small transistors in a bit cell.)

The decoder has an interesting electrical optimization. As shown earlier, the register select lines are eight polysilicon lines running vertically, the length of the register file. Unfortunately, polysilicon has fairly high resistance, better than silicon but much worse than metal. The problem is that the resistance of a long polysilicon line will slow down the system. That is, the capacitance of transistor gates in combination with high resistance causes an RC (resistive-capacitive) delay in the signal.

The solution is that the register select lines also run in the metal layer, a second set of lines immediately to the right of the register file. These lines branch off from the register file about 1/3 of the way down, run to the bottom, and then connect back to the polysilicon select lines at the bottom. This reduces the maximum resistance through a select line, increasing the speed.

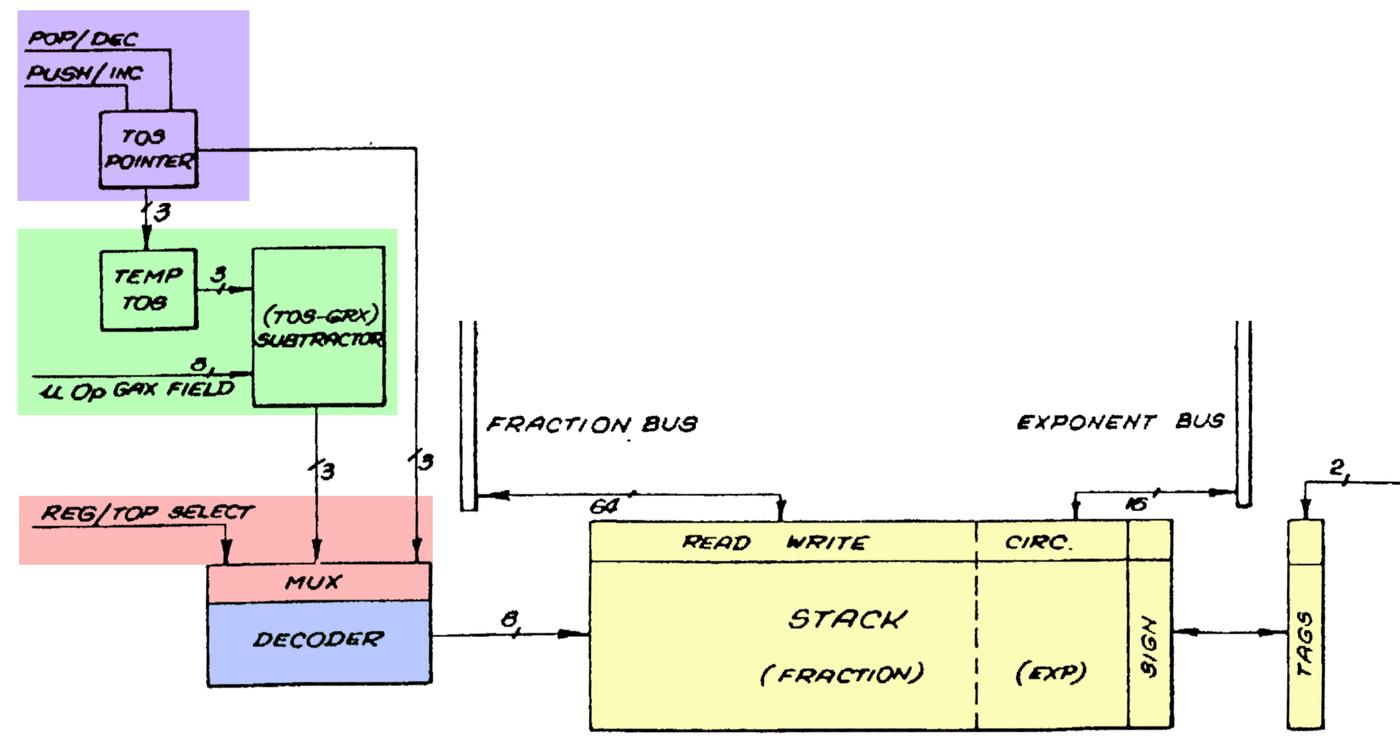

The stack control circuitry

A stack needs more control circuitry than a regular register file, since the circuitry must keep track of the position of the top of the stack.3 The control circuitry increments and decrements the top of stack (TOS) pointer as values are pushed or popped (purple).4 Moreover, an 8087 instruction can access a register based on its offset, for instance the third register from the top. To support this, the control circuitry can temporarily add an offset to the top of stack position (green). A multiplexer (red) selects either the top of stack or the adder output, and feeds it to the decoder (blue), which selects one of the eight stack registers in the register file (yellow), as described earlier.

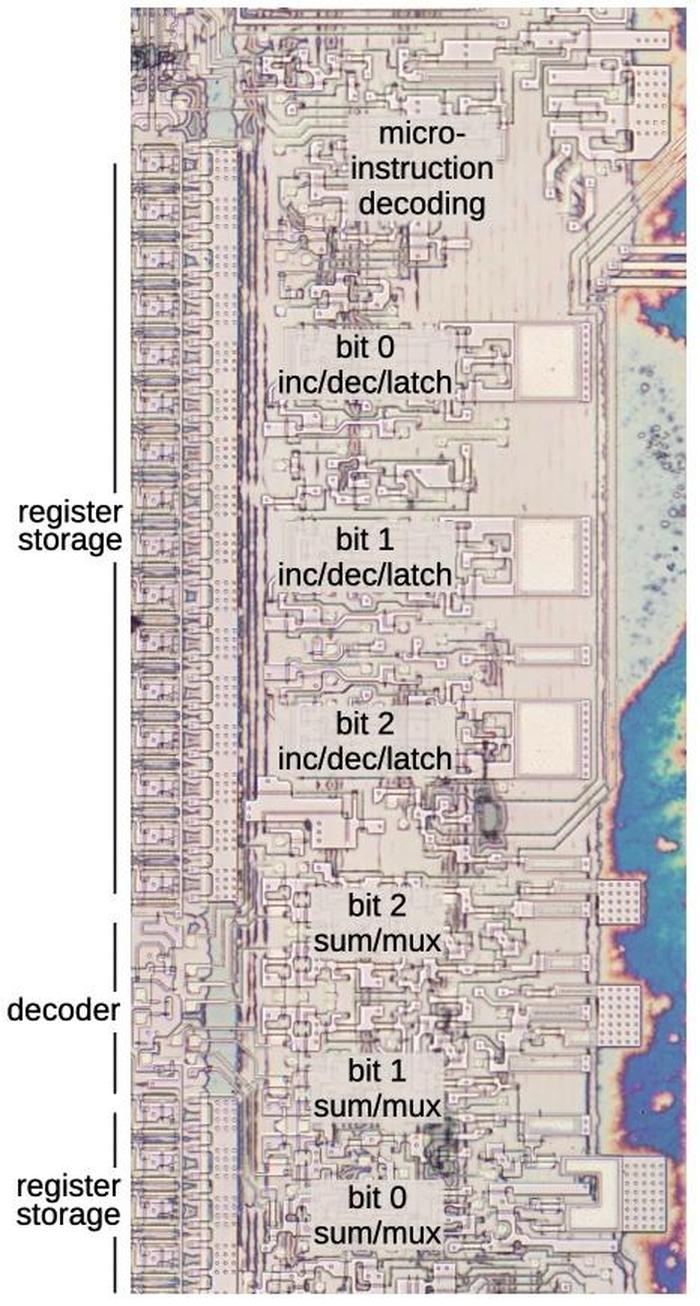

The physical implementation of the stack circuitry is shown below. The logic at the top selects the stack operation based on the 16-bit micro-instruction.5 Below that are the three latches that hold the top of stack value. (The large white squares look important, but they are simply "jumpers" from the ground line to the circuitry, passing under metal wires.)

The three-bit adder is at the bottom, along with the multiplexer. You might expect the adder to use a simple "full adder" circuit. Instead, it is a faster carry-lookahead adder. I won't go into details here, but the summary is that at each bit position, an AND gate produces a Carry Generate signal while an XOR gate produces a Carry Propagate signal. Logic gates combine these signals to produce the output bits in parallel, avoiding the slowdown of the carry rippling through the bits.

The incrementer/decrementer uses a completely different approach. Each of the three bits uses a toggle flip-flop. A few logic gates determine if each bit should be toggled or should keep its previous value. For instance, when incrementing, the top bit is toggled if the lower bits are 11 (e.g. incrementing from 011 to 100). For decrementing, the top bit is toggled if the lower bits are 00 (e.g. 100 to 011). Simpler logic determines if the middle bit should be toggled. The bottom bit is easier, toggling every time whether incrementing or decrementing.

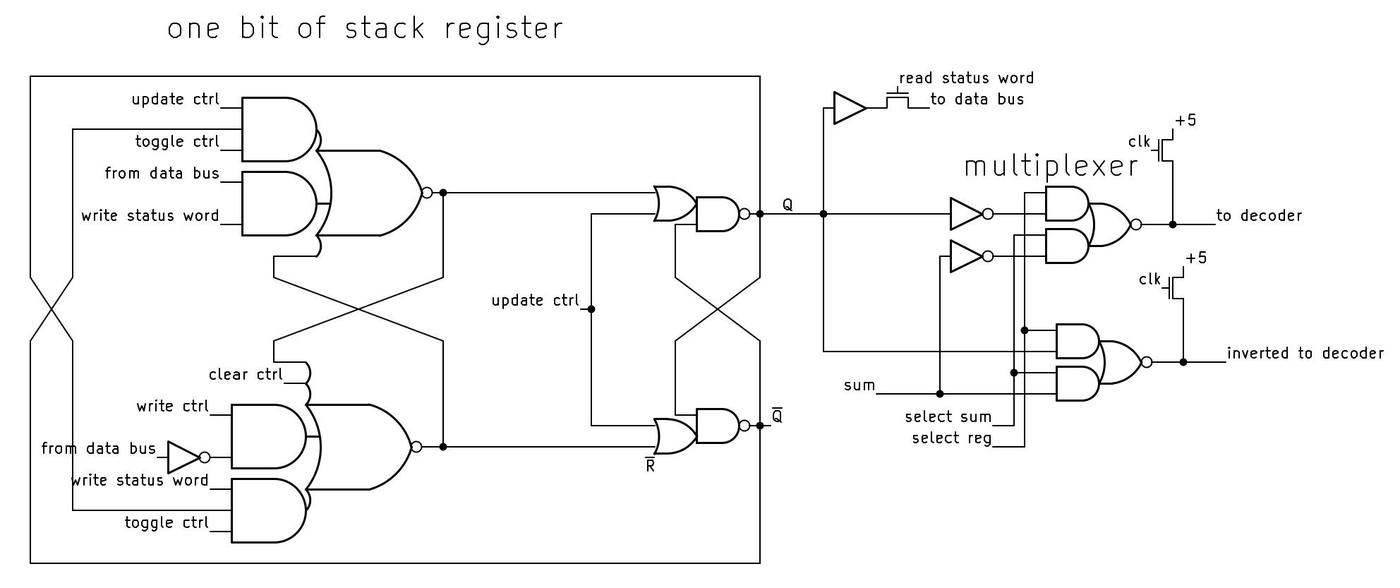

The schematic below shows the circuitry for one bit of the stack. Each bit is implemented with a moderately complicated flip-flop that can be cleared, loaded with a value, or toggled, based on control signals from the microcode. The flip-flop is constructed from two set-reset (SR) latches. Note that the flip-flop outputs are crossed when fed back to the input, providing the inversion for the toggle action. At the right, the multiplexer selects either the register value or the sum from the adder (not shown), generating the signals to the decoder.

Drawbacks of the stack approach

According to the designers of the 8087,7 the main motivation for using a stack rather than a flat register set was that instructions didn't have enough bits to address multiple register operands. In addition, a stack has "advantages over general registers for expression parsing and nested function calls." That is, a stack works well for a mathematical expression since sub-expressions can be evaluated on the top of the stack. And for function calls, you avoid the cost of saving registers to memory, since the subroutine can use the stack without disturbing the values underneath. At least that was the idea.

The main problem is "stack overflow". The 8087's stack has eight entries, so if you push a ninth value onto the stack, the stack will overflow. Specifically, the top-of-stack pointer will wrap around, obliterating the bottom value on the stack. The 8087 is designed to detect a stack overflow using the register tags: pushing a value to a non-empty register triggers an invalid operation exception.6

The designers expected that stack overflow would be rare and could be handled by the operating system (or library code). After detecting a stack overflow, the software should dump the existing stack to memory to provide the illusion of an infinite stack. Unfortunately, bad design decisions made it difficult "both technically and commercially" to handle stack overflow.

One of the 8087's designers (Kahan) attributes the 8087's stack problems to the time difference between California, where the designers lived, and Israel, where the 8087 was implemented. Due to a lack of communication, each team thought the other was implementing the overflow software. It wasn't until the 8087 was in production that they realized that "it might not be possible to handle 8087 stack underflow/overflow in a reasonable way. It's not impossible, just impossible to do it in a reasonable way."

As a result, the stack was largely a problem rather than a solution.

Most 8087 software saved the full stack to memory before performing

a function call, creating more memory traffic.

Moreover, compilers turned out to work better with regular registers than a stack,

so compiler writers awkwardly used the stack to emulate regular registers.

The GCC compiler reportedly needs 3000 lines of extra code to support the x87 stack.

In the 1990s, Intel introduced a new floating-point system called SSE, followed by AVX in 2011. These systems use regular (non-stack) registers and provide parallel operations for higher performance, making the 8087's stack instructions largely obsolete.

The success of the 8087

At the start, Intel was unenthusiastic about producing the 8087, viewing it as unlikely to be a success. John Palmar, a principal architect of the chip, had little success convincing skeptical Intel management that the market for the 8087 was enormous. Eventually, he said, "I'll tell you what. I'll relinquish my salary, provided you'll write down your number of how many you expect to sell, then give me a dollar for every one you sell beyond that."7 Intel didn't agree to the deal—which would have made a fortune for Palmer—but they reluctantly agreed to produce the chip.

Intel's Santa Clara engineers shunned the 8087, considering it unlikely to work: the 8087 would be two to three times more complex than the 8086, with a die so large that a wafer might not have a single working die. Instead, Rafi Nave, at Intel's Israel site, took on the risky project: “Listen, everybody knows it's not going to work, so if it won't work, I would just fulfill their expectations or their assessment. If, by chance, it works, okay, then we'll gain tremendous respect and tremendous breakthrough on our abilities.”

A small team of seven engineers developed the 8087 in Israel. They designed the chip on Mylar sheets: a millimeter on Mylar represented a micron on the physical chip. The drawings were then digitized on a Calma system by clicking on each polygon to create the layout. When the chip was moved into production, the yield was very low but better than feared: two working dies per four-inch wafer.

The 8087 ended up being a large success, said to have been Intel's most profitable product line at times. The success of the 8087 (along with the 8088) cemented the reputation of Intel Israel, which eventually became Israel's largest tech employer. The benefits of floating-point hardware proved to be so great that Intel integrated the floating-point unit into later processors starting with the 80486 (1989). Nowadays, most modern computers, from cellphones to mainframes, provide floating point based on the 8087, so I consider the 8087 one of the most influential chips ever created.

For more, follow me on Bluesky (@righto.com), Mastodon (@[email protected]), or RSS. I wrote some articles about the 8087 a few years ago, including the die, the ROM, the bit shifter, and the constants, so you may have seen some of this material before.

Notes and references

-

Most computers now use the IEEE 754 floating-point standard, which is based on the 8087. This standard has been awarded a milestone in computation. ↩

-

Curiously, reliable sources differ on the number of transistors in the 8087 by almost a factor of 2. Intel says 40,000, as does designer William Kahan (link). But in A Numeric Data Processor, designers Rafi Nave and John Palmer wrote that the chip contains "the equivalent of over 65,000 devices" (whatever "equivalent" means). This number is echoed by a contemporary article in Electronics (1980) that says "over 65,000 H-MOS transistors on a 78,000-mil2 die." Many other sources, such as Upgrading & Repairing PCs, specify 45,000 transistors. Designer Rafi Nave stated that the 8087 has 63,000 or 64,000 transistors if you count the ROM transistors directly, but if you count ROM transistors as equivalent to two transistors, then you get about 75,000 transistors. ↩

-

The 8087 has a 16-bit Status Word that contains the stack top pointer, exception flags, the four-bit condition code, and other values. Although the Status Word appears to be a 16-bit register, it is not implemented as a register. Instead, parts of the Status Word are stored in various places around the chip: the stack top pointer is in the stack circuitry, the exception flags are part of the interrupt circuitry, the condition code bits are next to the datapath, and so on. When the Status Word is read or written, these various circuits are connected to the 8087's internal data bus, making the Status Word appear to be a monolithic entity. Thus, the stack circuitry includes support for reading and writing it. ↩

-

Intel filed several patents on the 8087, including Numeric data processor, another Numeric data processor, Programmable bidirectional shifter, Fraction bus for use in a numeric data processor, and System bus arbitration, circuitry and methodology. ↩

-

I started looking at the stack in detail to reverse engineer the micro-instruction format and determine how the 8087's microcode works. I'm working with the "Opcode Collective" on Discord on this project, but progress is slow due to the complexity of the micro-instructions. ↩

-

The 8087 detects stack underflow in a similar manner. If you pop more values from the stack than are present, the tag will indicate that the register is empty and shouldn't be accessed. This triggers an invalid operation exception. ↩

-

The 8087 is described in detail in The 8086 Family User's Manual, Numerics Supplement. An overview of the stack is on page 60 of The 8087 Primer by Palmer and Morse. More details are in Kahan's On the Advantages of the 8087's Stack, an unpublished course note (maybe for CS 279?) with a date of Nov 2, 1990 or perhaps August 23, 1994. Kahan discusses why the 8087's design makes it hard to handle stack overflow in How important is numerical accuracy, Dr. Dobbs, Nov. 1997. Another information source is the Oral History of Rafi Nave ↩↩

5 comments:

I worked on the Intel iAPX 432 project for nearly four years as a lead technical writer, on the subsequent Gemini/BiiN project that developed the i960 from its inception as manager of technical publications/writer/writing team manager, and later wrote the Intel 960 Extended Architecture Programmer's Reference Manual on contract to Intel. The 8087 was an important foundation, as IEEE floating-point was supported in both the 432 chips and in most of the i960 chips. (The i960 core architecture did not support floating-point in hardware; the numerics, protected, and extended architectures did.) I always appreciate your posts. Sincerely, Martin L Buchanan/[email protected].

I’ve had the opportunity to work closely with Intel’s processor architecture over the years. I spent nearly four years on the Intel iAPX 432 project as a lead technical writer, then continued on the Gemini/BiiN project—where the i960 originated—as the manager of technical publications, writer, and writing team lead. I later authored the Intel 960 Extended Architecture Programmer's Reference Manual as a contractor.

The 8087 also played a key role, since IEEE floating-point was supported in both the 432 family and most versions of the i960 (with floating-point implemented in the numerics, protected, and extended architectures).

Really appreciate your posts—always insightful.

I think one of the problems about the stack design is that it made it difficult to read fpu code and understand what it was doing, you really had to concentrate and think about each line. Today I wasted a day tracking down a bug in legacy x86 fpu code that I have to convert to x64 SSE and it turned out to be due to a partial calculation that was left on the stack and then re-used a couple of hundred instructions later! So I specially loved learning about the stack in your article. Thanks and keep up the good work

You say that: "I don't know what the GRX field is."

Isn't it the "R" field ("reg") of the ModRM byte?

In the data sheet https://datasheets.chipdb.org/Intel/x86/808x/datashts/8087/205835-007.pdf, on page 20, I see the opcode for FADD, for example. With MOD = 11, the R/M bits are the i of ST(i) if I read it correctly.

This is also true for other commands like FLD, FST(P), FCOM(P), FSUB and FFREE.

Adder or subtractor would not make any difference other than the way the stack is organized - or does it allow direct access to registers other than relative?

My personal beef with the 8087 stack comes from when I was trying to write optimized floating point assembly code for the original Pentium processor. There were definitely some potential gains to be had by not ordering your computations in stack order, I think some things could run in parallel? To accommodate such optimisations, Intel noted helpfully that a floating point instruction in the U pipe would pair with an FXCH instruction in the V pipe, and issue in the same cycle. So I tried to write code that used that "free" stack exchange instruction every cycle to effectively have floating point instructions that could choose both their register inputs. But I think I gave up pretty quickly, because it was utterly confusing...

Post a Comment